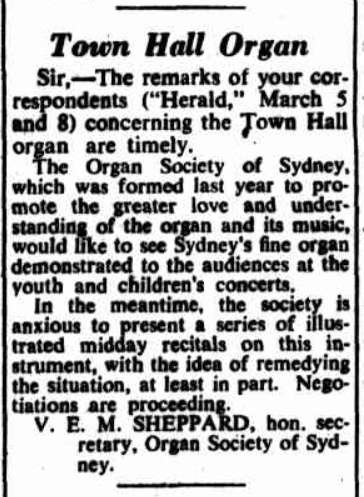

Being an organ student at St John’s Anglican Cathedral, Parramatta I’ve had some opportunities to meet and interact with other organists in Sydney, and particularly those who are members of the Organ Music Society of Sydney (OMSS). I thought it would be a worthwhile and relevant pursuit to complete a project with the Society that would benefit them. Seeing that the OMSS website did not include significant historical detail I initially envisioned making a timeline – of particular benefit as 2020 is the 70th Anniversary year of the Society.

My regular contact, committee member and Sydney Organ Journal editor Peter Meyer, conveyed to me a few topics that the Society were interested in researching. These included: a report on the impacts of CoViD-19 on the Society; a survey of achievements of members, particularly those who took up organist positions internationally; or a discussion of the impact of prizes and grants on recipients (mostly students), particularly as these have seemed to increase in value over time. Reflecting on my original idea for a timeline, Peter suggested that this would be difficult to research in the time I had available due to the large number of past Journals (at least 50 years’ worth) and the lack of insight I might have on my own to identify important events. I also was not able to find many significant sources that cover the history or activities of the OMSS from its founding in 1950 until 1970 when the Journal was first published.

While still formulating my mode of research, Peter invited me to attend the 3rd annual ‘Organ Spooktacular’ concert on October 30th hosted by current and former organ students of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music in support of Headspace. During the concert and subsequent discussions held with the performers over dinner, I was inspired to meld my research on the Society’s history around the experiences of young organists over its lifetime. Though my article would be focussed on this topic, I also had opportunity through that lens to include many of the other areas that the committee also wished to investigate. A written report, which could be published in article form through the Sydney Organ Journal to all members, seemed like the best approach by which to distribute my work to those interested in the OMSS’ history and others such as students who are indirectly linked through teachers who are members.

I have worked substantially on my article for the Society but am still at the stage of completing my first draft. I have yet to access copies of the Sydney Organ Journals archived at the Mitchell Library and a range of other documents that cover histories of the OMSS and sister organisation, the University of Sydney Organ Association, through the 1960s and 70s. I utilised a Google Form survey to begin a process of obtaining oral histories that was distributed to Society members, teachers, and students and which worked very well as a method of contact to gain initial insights. I have received 25 responses so far!

My report will show that the OMSS has done significant work to improve the regularity and accessibility of organ playing since 1950 and to support young organists through initiatives such as the Young Organists Day, Sydney Organ Competition, and various organ academies. I will also conclude with a section to encourage reflection on the future of the Society and the work it might choose to do as organ music still remains out of the spotlight for many in Sydney. Survey responses indicated that Australia in particular (compared to places like Europe and the US) is seeming to take organists and their roles in worship leading and public performance increasingly less seriously. I think that the method I took of shaping my project around oral histories and insights of Society members will be hugely beneficial to its final impact for readers, and reflects themes learnt during this semester. We discussed in class how oral histories reveal unique and personal engagement with events, and the ways that objective events are made significant by how people experience them. I have attempted to include historiography and debate where applicable, such as the contemporary ‘Organ Reform Movement’ during the beginnings of the Society. Research of the OMSS has been tricky as it is an umbrella organisation with many overlapping groups such as the Organ Historical Trust of Australia, students and teachers at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, the University of Sydney Organ Association, or the Royal School of Church Music Australia etc. I haven’t found significant sources with cohesive records of the OMSS and its activities, though hope that further research of the Fisher Library archives or Sydney Organ Journals will be insightful.

I am hopeful that my completed report will provide a unique reflection on young organists and the culture of the OMSS with consideration of the Society’s future. I wish still to include further integrated insights from Society members through follow-up discussions based on survey responses. I also hope to include additional historical detail that will bring fullness to the article and meet its original aims as a public history project. The process of completing this project has been very interesting and rewarding, and I hope to share my research with the Society in due course.