In conjunction with the conference ‘What is International History Now?’, the Laureate Research Program in International History, University of Sydney, is convening a Research Laboratory on the past, present and future of International History on Monday 23 July 2018.

Interested students and ECRs in History, I.R., Law, or other relevant disciplines can apply for a place in this ‘laboratory’ featuring:

Matthew Connelly, Columbia University

Peter Jackson, Glasgow University

Sandrine Kott, Geneva University

Dirk Moses, University of Sydney

Patricia Owens, Sussex University

Davide Rodogno, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Glenda Sluga, University of Sydney

The laboratory is part of the ‘What is International History Now?’ conference to be held from Monday 23 – Friday 27 July.

It includes a public panel and reception on the Monday evening, opportunity to participate in a breakfast seminar on ‘International Thinking’ with Profs Anne Orford (Melbourne); Chris Reus-Smit (UQ); Patricia Owens (Sussex University); David Armitage (Harvard) and Breakfast seminar the next morning, Tuesday 24 July.

We encourage early career scholars completing PhDs, Postdocs, ECRs to apply. Please send a bio and statement of interest (one page only) to beatrice.wayne@sydney.edu.au by end of May 31, 2018.

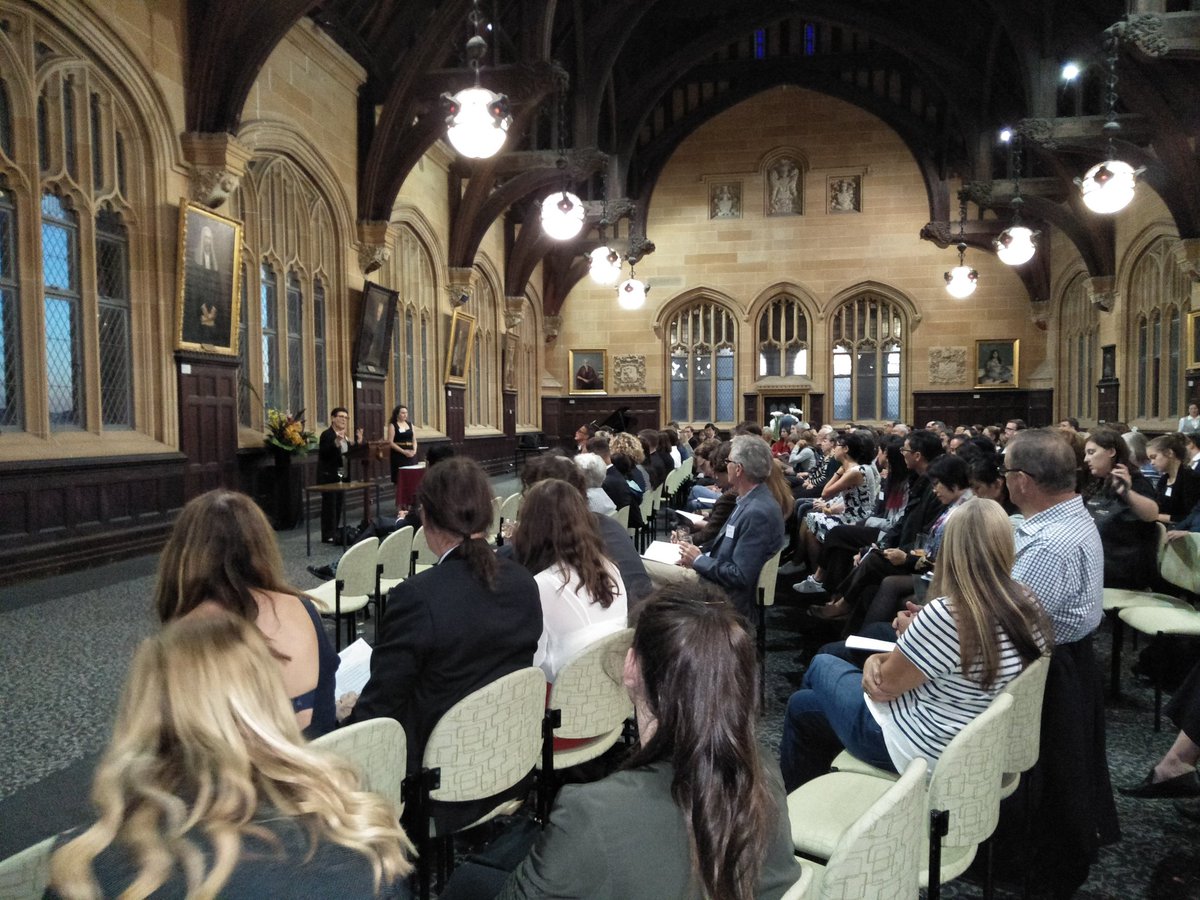

Graduation Ceremony May 2, 2018

The Department would like to offer a warm congratulations to all of our students who graduated recently.

These included six new PhD recipients: Sarah Bendall, Billy Griffiths, Mick Warren, Nick Irving, James Findlay, and Kim Kemmis. And two new MAs, Rainald Roesch and Anne Armistead-Higgins.

The graduating cohort also included close to forty History Honours and BA students, including University medal winner Alexander Jackman.

Many congrats to all on your achievements and good wishes for your future endeavours.

The occasional address was given by Professor Michael A. McDonnell from the Department of History. A transcript of his speech can be found here.

HIstory Awards for 2017

The Department of History at the University of Sydney would like to offer warm congratulations to the History Department Prize winners, who received their awards at the annual SOPHI Prize Ceremony on Tuesday May 1. And thanks to award-winner Sarah Charak for her wonderful speech that evening. Given the hundreds of students in our history classes, and the quality of so much of their work, winning these prizes is a huge accomplishment. Again, many congratulations to all.

The winners were as follows:

A.E. (Tony) Cahill History Prize – Samuel Goldberg

Aisling Society of Sydney Prize for an essay on Irish or Irish-Australian History – Ciara Smart

Charles Trimby Burfitt Prize for the Study of Australian History Prior to 1900 – Jeanne Apolonio

Ernest Bramsted Prize for Modern or Medieval European History – Emily Paget

George Arnold Wood Memorial Prize for History I – Samuel Goldberg

George Arnold Wood Memorial Prize for History II – Xanthe Peta Robinson

George Vari Prize For History And Medieval Studies – Jemimah Back and Nicole Leong

GS Caird Scholarship in History II – Colin Taylor

Helen Newbon Bennett Memorial Prize for Senior History – Pola Cohen

History Department Prize for outstanding work in HSTY3901 – Alison Lee

History Department Prize for outstanding work in HSTY3902 – Sarah Charak

History Department Prize for outstanding work in HSTY3903 – Sally Ghattas

History Department Prize for an outstanding essay on a subject relating to social justice and/or social inclusion – Ashleigh Taylor

Isabel M. King Memorial Prize for History III – James Collier and Daniel Swain

J.H.M. Nolan Memorial Prize for Proficiency in History – Sarah Charak – Student speaker

Maud Stiles Memorial Prize in Senior History – Radha Wahyuwidayat

Philippe Erdos Prize in History – Alexander Jackman

Stage 4 Open Day with Cecil Hills

On the 6th of April, 50 students from Chifley College public school came in busloads to campus. This was for the Stage 4 Social Inclusion in History Open Day for 2018. The purpose of open days like this is to introduce the idea of studying at university to students for whom this may not be the typical trajectory.

The day started with a welcome by Michael McDonnell. He spoke of the importance of education and how it can enhance the quality of life and opportunities for persons from a range of backgrounds. The students were split into four groups, and participated in four different educational and historical activities in a round robin. A campus tour was led by USYD student volunteers, who showed the high school students their favourite places on campus. The students experienced a treasure hunt and historical quad tour, as well as a talk about First Nations history in Sydney. After lunch, there was a theatrical demonstration by the Society for Historical Anachronism. All the students received show bags before a final wrap up.

The day only came together with the help of the amazing USYD student volunteers who led the teams. As well as the co-operation from Cecil Hills’ teachers, and our experts Craig Barker and Simon Wyatt-Spratt.

The teachers and students were incredibly pleased with the outcome of the day. Cecil teacher Steffanie Haskett expressed to us that introducing kids to university at this point of their education can make a crucial difference to decision-making later.

We will be following this up with a Stage 5 Open Day in July!

History Workshop – A New Era in History at Sydney

In March 2018, new undergraduate students at the University of Sydney will be taking part in a bold experiment in history education, where they will begin unravelling the racial dynamics of depression-era La Perouse or the crackdown on communists in 1920s Shanghai.

As part of the University’s reimagined undergraduate curriculum, the Department of History has developed new units of study about world history and a new unit unlike any other taught in an Australian university: HSTY1001 History Workshop.

Read more

Student Equity Alliance debuts at O-Week

For the first time at O week, a student society which focuses on bringing together students that are First in Family to attend university, or are from a low socioeconomic background, was showcased. The “Student Equity Alliance” (SEA). The society aims to start the conversation about the experience of students who fall into this category, to build a community for these students (who can be very isolated by the prestigious nature of University of Sydney), and to encourage the University to be more systemically supportive of their low ses student population.

The society has been started by students Shayma Taweel and Bridget Neave, the previous and current Project Managers for Social Inclusion in History respectively. Mike Mcdonnell and Frances Clarke have been supporting Bridget and Shayma in their endeavour to set up a student community around this social issue through the Social Inclusion Committee.

The society is off with a bang with 40 members in its first week in action!

Staff are also encouraged to become a part of this community, Bridget and Shayma invite you to like the Facebook page and come to events to be announced in future.

Pictured above are Bridget Neave (SEA President) and Jordan Watkins (representative of the student-managed affordable housing co-op – STUCCO) at O week.

New Staff and Teachers for 2018

Dear Historians,

This semester we welcome some familiar faces to new roles in the department, and one new colleague who’ll be with us for the academic year.

Dr Aminat Chokobaeva joins us from the ANU. She’ll be teaching HSTY2659 Nationalism in semester 1 and HSTY2613 Russia’s Revolutions in semester 2.

Dr Emma Barron, who earned her PhD in the department in 2016, is returning to teach HSTY2608 European Film and History.

Ben Vine, who has just submitted his PhD thesis, is teaching HSTY2666 American Revolutions.

Dr James Dunk, who has been working in REGS for the last few years, is teaching HSTY2304 Imperialism.

Dr Mick Warren, who will be in Mark McKenna’s office while Mark is away this year, is teaching the Great Barrier Reef OLE and a winter intensive in Australian history.

Minerva Inwald, who is holding a FASS teaching fellowship this year, is teaching a seminar in HSTY1001.

Welcome, everyone. It’s great to have you with us.

Chris

CHRIS HILLIARD | Professor of Modern British History

Chair, Department of History | Main Quadrangle A14

The University of Sydney | NSW 2006 | Australia

Cecil Hills High School Mentoring 2018

On Tuesday, February 13, seven volunteers from the University of Sydney ranging from undergraduate to postgraduate student visited Cecil Hills High School to kick off our 2018 History Extension Mentoring Program.

This is the second year we have run the program with Cecil Hills and we were delighted to see that the program had grown from three students to eight this year.

In this session, the students gave our mentors a tour of the school, introduced themselves and their chosen topics, and then worked one on one with the volunteers to refine their questions and think about sources. The topics ranged widely, from representations of Cleopatra and Catherine de Medici in history and film, to communist art in China, to genocide in Serbia. The mentors were impressed by the students’ interests, and knowledge.

The program consists of five school and university visits over a six-month period, where the mentors also provide guidance on applying to and studying at university. We are looking forward to hosting the students here at the University of Sydney in March, when they will meet up with their mentors and get a chance to tour the campus before doing some research in the library.

Department of History Seminar Series, Semester One 2018

Dear colleagues and friends of the History Department, University of Sydney

In 2018 our departmental seminar will be moving to a different day of the week and will be held at intervals across the semester rather than weekly. The venue remains the same. Details of this semester’s program for History on Wednesday can be found below and the full program is on the web here:

Seminar Series for Postgraduates and Faculty

Held at 12.10-1.30

in Woolley Common Room, Woolley Building A22

(Enter Woolley through the entrance on Science Road and climb the stairs in front of you. Turn left down the corridor, and the WCR is the door at the end of the hall)

Coordinators:

Dr Andrés Rodriguez and Professor Kirsten McKenzie

Semester 1 2018

7 March

Marco Duranti (University of Sydney)

French Colonialism and International Human Rights after 1945

21 March

Peter Hobbins (University of Sydney) and Elizabeth Roberts-Pedersen (University of Newcastle)

False horizon: historical data, the psychology of risk and the politics of safety

18 April

Penny Russell (University of Sydney)

Family Business: Love and Money in Colonial Sydney

2 May

Paul Betts (Oxford University)

Red Globalism: Eastern Europe, Decolonization and African Heritage

16 May

Elizabeth Manley (Xavier University of Louisiana)

Created by God for Tourism: Developing Tropical Paradise in the Dominican Republic, 1966 – 1978

23 May

Chris Hilliard (University of Sydney)

Housing, Race and the Remaking of the English Working Class

Recent Completions

In February, Sarah Dunstan received word that she had successfully passed her PhD. Sarah’s dissertation, completed under the direction of Shane White, is entitled “A Tale of Two Republics: Race, Rights, and Revolution, 1919-1963.” Her reports were unanimous that the dissertation needed no more revision and was ready to be accepted immediately. One reviewer noted that ” This is an extraordinarily ambitious study, which addresses multiple histories, multiple historiographies, and multiple scholarly audiences,” while another pointed to how “she skillfully distributes (her research)…through an ambitious synthetic narrative that spans most of the 20th century and encompasses a wide range of actors, movements, ideologies, debates and events not only in France and the United States but in French Caribbean and African colonies as well.” A glimpse of some of her work can be found in a recent blog post she wrote for the Journal of the History of Ideas. Please join us in congratulating Sarah.

Many congratulations to Sarah Anne Bendall for the successful submission of her Ph.D. thesis, entitled “Bodies of Whalebone, Wood, Metal, and Cloth: Shaping Femininity in England, 1560-1690,” which she completed under the direction of Dr. Julie Ann Smith. Sarah’s reviewers were universally impressed by her research and writing, with one noting the thesis “is sophisticated, wide-ranging and highly ambitious in scope,” another calling it “one of the best I have read to date,” while the third heaped praise on her nuanced argument and substantial research. Some of the innovative work she did for her thesis can be found on her blogsite. Please join us in congratulating Sarah on her incredibly impressive achievement.