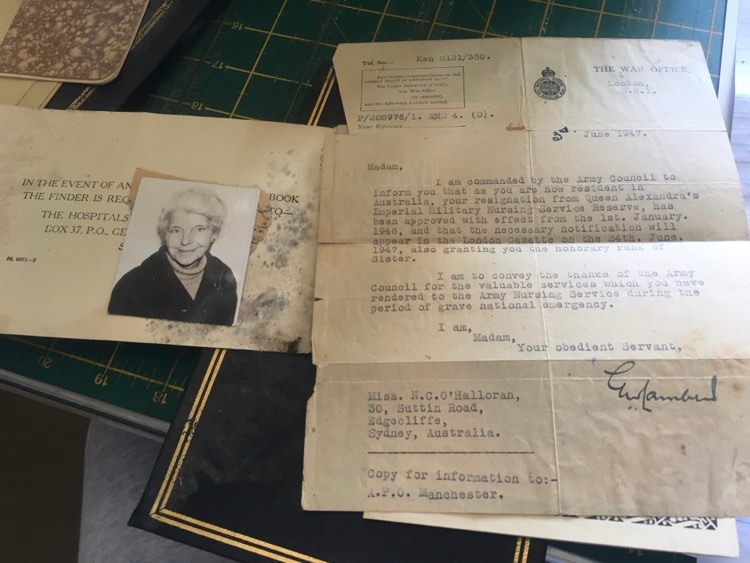

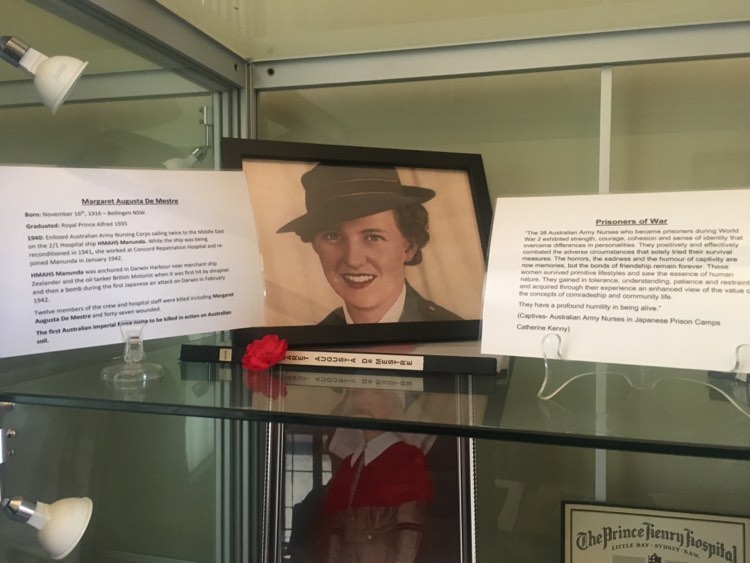

For my final project with the Sydney Jewish Museum, I compiled a 14-paged ‘education resource package’ on the stories of post-war Jewish migration to Australia, consisting of curriculum links, background content information, lesson plans and source booklets for teachers. Though this project only forms one part of a larger collection of pre-existing educational resources at the Museum, I focused on identifying and addressing the gaps in the repository of resources – those that are overlooked even by professional historians and educators, within such a fast-paced, busy organisation environment. For instance, not all on-site excursion programs have a complimentary lesson plan; resources tend to cater for ‘mainstream’ students than providing differentiation options for various ability levels; and all existing lesson plans focus on explaining the Nazi regime and political motivations behind the genocide, at the expense of telling further Jewish stories. In this regard, my project is significant to the Museum as a starting point to the longer, nascent endeavour to address these gaps in resources and ensure accessibility for a wider audience of students.

This project argues that the purpose of history is the preservation of stories from the past through the education of the future generations. The greater vision of the SJM Education Team and the Museum wholly is to preserve the voices of the past in light of the dwindling population of Holocaust survivors – and at the core of this mission is to educate and transmit the Holocaust memory to students, who are our emerging historians. It is not only crucial to ensure this education is accessible to as many students as possible, but is also engaging, for conversations to continue history beyond the classroom (pun intended) and preserve the Holocaust past in the public memory.

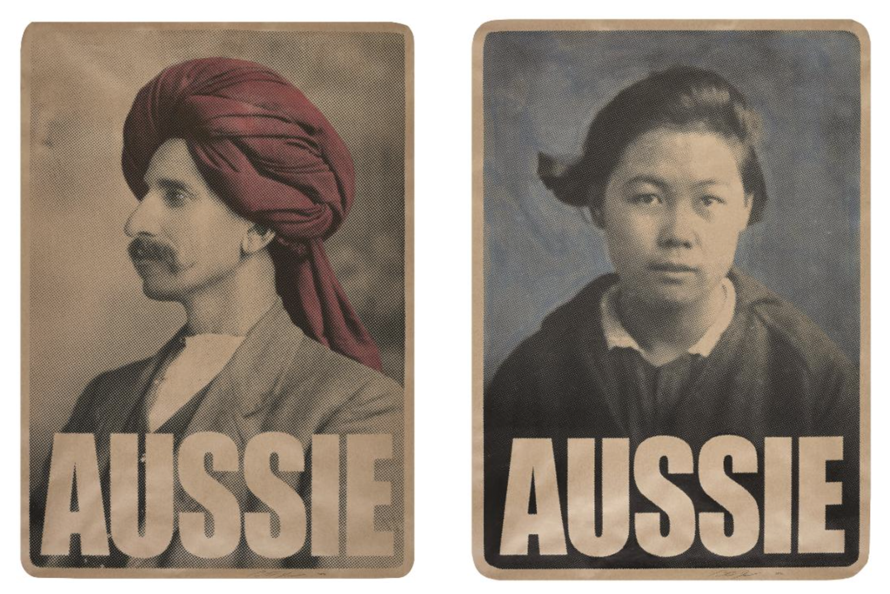

After publishing my project on the Sydney Jewish Museum website, the project will therefore benefit teachers, who frequently contact the Museum asking for resources that could extend student knowledge following an on-site excursion visit. It also will benefit students, as it provides various engaging yet enriching history pedagogies to understand the past. The resource is specifically targeted at Stage 5 students studying Migration Stories, though the difficulty of activities can be tailored to the age group and needs of students attending the on-site program. Overall, the resource ensures that students are well-equipped to preserve and further transmit the Holocaust and Jewish memory, and continue significant conversations that draw connections between the past and the present national identity and Australian Judaica.