Located in Darling Harbour, Sydney, right next to the sea, the Australian National Maritime Museum – or the Sea Museum, as it’s more colloquially known – tells the history of our nation.

For people who are unfamiliar with the Sea Museum – such as myself at the beginning of this project – they will be surprised to find out about the complexity of knowledge that is on offer at the Sea Museum. As counterintuitive as it may sound, the Sea Museum is much, much more about ships and boats. Ranging from maritime archaeology, historic vessels, to ocean science, Indigenous culture, and migration, the Sea Museum has it all.

Among these vastly diverse topics, my project, in collaboration with the Sea Museum, particularly focuses on migration. How does migration and the Sea Museum link together? You may ask. Well, as a nation that’s mostly made up of migrants, it is important for us to know how did the early migrants come to Australia, and the stories happened along the way and afterwards. And the sea of course plays an important role here. Therefore, as one of the only six museums operated by the federal government, the Sea Museum bears the responsibility of educating the public the stories about the nation and the people who made up our nation.

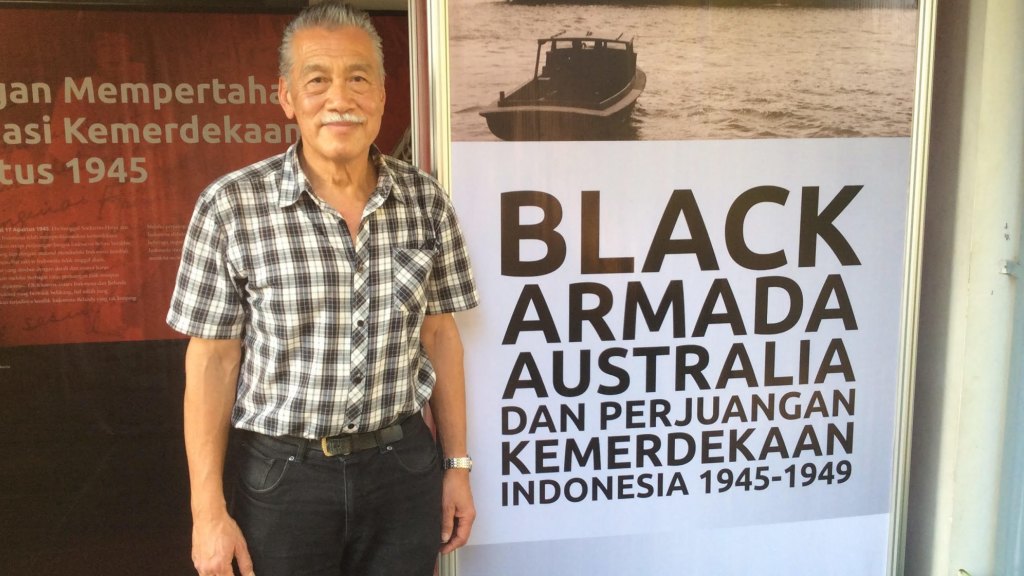

The stories I want to tell in my project are of Anthony Liem, and Fred Wong and Arthur Chang. Anthony is a Chinese Indonesian. Although he was barely three years old at the time, he remembers Indonesian people’s fight for independence vividly. Because of the anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia, he migrated to Australia and later married Helen Wong, an Australian-Chinese woman. But it wasn’t until somewhat three decades after they married, in 2005, did he discover the shared history between Helen and him.

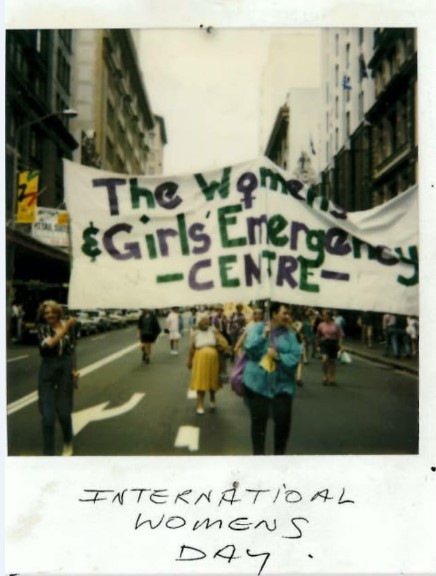

Both Helen’s father, Fred Wong, and his friend Arthur Chang, were active members of the Chinese Youth League and the Sydney branch of the Chinese Seaman’s Union (disbanded in the late 1940s). Both organisations were made up of patriotic Chinese Australians who supported China’s fight against Japan’s colonial power, and were sympathised with, and actively supported the Indonesian independence movement.

Arthur, as a representation of Chinese seamen, spoke to a packed audience and appealed for the public’s support, which was captured in the documentary Indonesian Calling. Quoting the “national father” Dr Sun Yat-sen that China would support all oppressed nations to gain independence, Arthur chanted, “Long live the independence movement,” and in Cantonese, “Long live the national liberation movement (民族自由解放运动万岁)”.

Despite being awarded the Centenary Medal of Australia for services to the Chinese community by the Australian government, and presented with the “70th Anniversary of The Victory of The Anti-Japanese War Commemoration Medal” by the Chinese government, Arthur’s story – and Fred’s – was totally unknown to me and many others.

So, for my project, I will speak to Anthony to get to know these stories better. We will talk about his memory of the Indonesian independence movement, living in a “White Australia”, and his thoughts on Fred’s and Arthur’s activism. A research paper will be developed based on the interview and my research, the end product might be published on the Sea Museum’s quarterly magazine Signals.

When I was doing research for the project, and typed in the words “Chinese Australian” and “Indonesian independence”, I was surprised to see how few relevant results I got. Among the limited information I got, the ones that matched my interest – most of them, if not all – come from the Sea Museum. Let’s say, even if I had uncertainties about this project at the beginning – not saying that I had any – this discovery only made me more firmly believe in it. As historians, it is our responsibility to tell the stories of our predecessors.

Old soldiers may die, but they should not fade away.