For the final research project, I worked with the Australian National Maritime Museum on the topic of Australia’s Indonesian independence movement – a past that shaped Australia’s national identity, but is not known to the Australian public. For the final project, I conducted an oral history interview and wrote a research paper based on the interview and other academic sources. Although the contents of my project are rather conventional, comparing to my fellow classmates’, the topic I discussed was not even a bit less fascinating.

It was in 1945, only two days after the Japanese Emperor announced its surrender, Indonesian nationalists declared the independence of Indonesia, after colonised by the Dutch for three and a half centuries. But the declaration of the independence was not enough, it took the Indonesians four years and countless casualties to achieve their independence. But they were not alone in their fight for independence. Across the Timor Sea, people in Australia were also fighting for Indonesian’s independence in Australia.

Australia’s support for the Indonesian independence movement was significant, not only for an independent Indonesia, but also for the construction of a modern multicultural and independent Australia. Activists in Australia’s Indonesian independence movement came from different cultural backgrounds – Indonesians, Indians, Chinese and Australians. They united together for a shared cause, a rare scene at a time when the White Australia Policy was still in place. In supporting the Indonesian independence, the Australian government under Prime Minister Ben Chifley went against orders from the “Motherland” Britain. This was an important event in Australia’s history, symbolising the separation from its coloniser, and the beginning of an independent Australia, over forty years after the foundation of the Australian Federation.

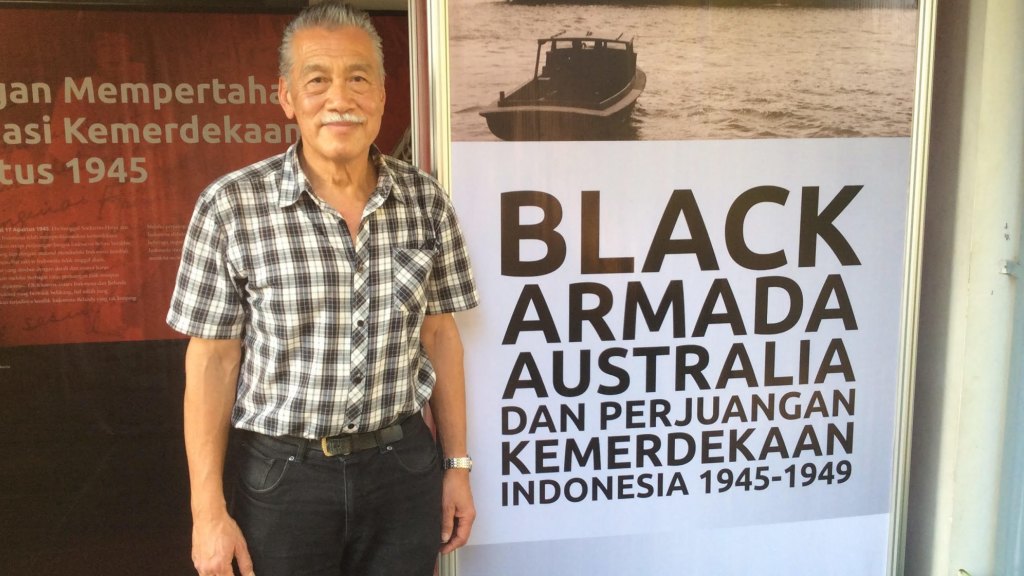

In order to discuss this past, I conducted an oral history interview with Anthony, an Indonesian Australian, who not only have extensively researched on this topic for over a decade, but also have a personal connection with it. Anthony’s father-in-law, Fred Wong, was a leader of Sydney’s Chinese Australian community in the 1940s, and organised the Chinese Australians’ support for the Indonesian independence movement.

In the research paper, I combined both personal history of Fred Wong and the broader political history at the time, argued that Australia’s support for the Indonesian independence movement was a significant event in Australia’s history that should be known to the Australian public.

Despite the significance of this past, few people – in the Indonesian, Chinese, or the Australian societies – know about it, even academic discussion around this topic is limited. Therefore, I suggested that given museum’s vital role in educating the public and constructing public memory, there should be a permanent exhibition on this past and the activists behind it in a major Australian museum.

Thank you to the Maritime Museum and my interviewee Anthony for introducing me to this fascinating past that is so important to our identity. Thank you to the History Beyond the Classroom unit for the opportunity to explore the world of history outside the university campus.