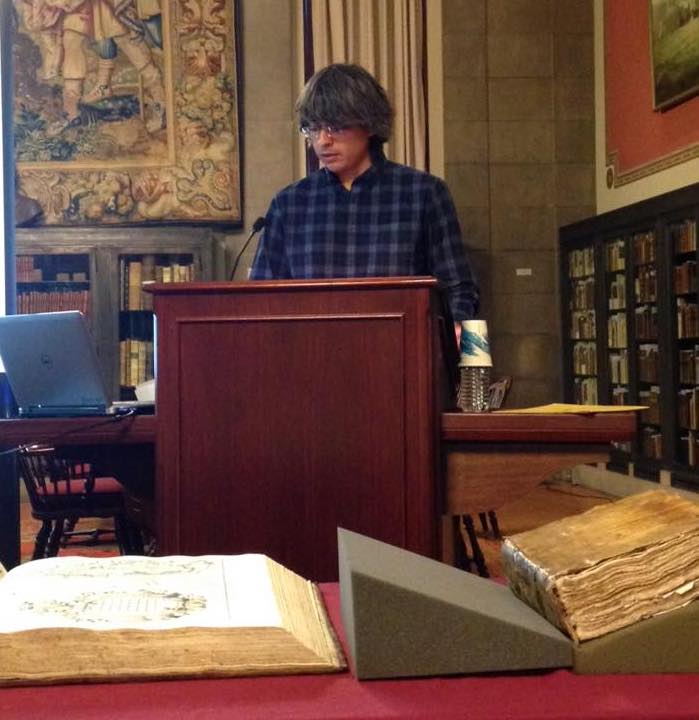

On Wednesday, September 7, 2021, Dr. Thomas Adams spoke about his role in the Street Re-Naming Commission in New Orleans in the Department of History’s “In Print and in Prospect” seminar series. The Department also bid farewell to Thomas as his resignation brought to an end six years of service at the University of Sydney.

Colleague and friend, Associate Professor Frances Clarke, took the opportunity to say a few words about Thomas’ tenure at Sydney, and his many contributions the Department.

Here is a transcript of Associate Professor Clarke’s speech:

It’s striking to think that Thomas only started work at the University of Sydney in 2014. That means that it has only been 6 years between his arrival here, and his return to the US, right before the pandemic hit. For those 6 years, he worked in both the History Department and the U.S. Studies Center. Given that Thomas worked across these two locations, you might not be aware of all he was during this short period. I’d like to spend a few moments acknowledging some of that work, because it’s a remarkable record. I’ll start with teaching.

From arrival to departure, Thomas taught 12 unique first- and second-year units:

At first year:

Lincoln to Obama

History Workshop: Chicago 1968

At second and third year:

American Social Movements

The History of Capitalism

History and Historians

African American History and life

Law and Order in American History

New Orleans: Disaster, Culture and Identity

The American Studies Capstone Seminar

Foreign Policy, Americanism and Anti-Americanism

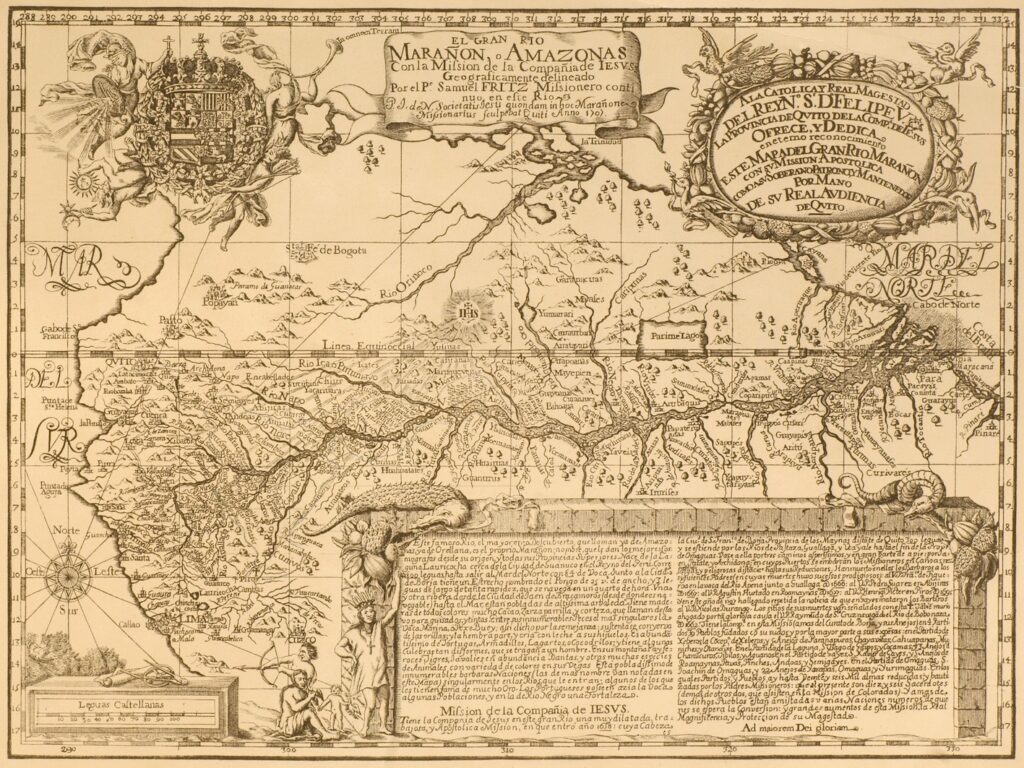

Latin American Revolutions

Unnatural Disasters

Some of these were history courses, and others were taught through the U.S. Studies Center. They equate to 2 new units every single semester he was here—a record that is unmatched by any other academic I know. It speaks to Thomas’s breadth of interests and versatility, not to mention his willingness to step into whatever roles needed filling.

In addition to this teaching, he was helping to train our postgraduate students. In 2014, not long after his arrival, he and I ran an American Studies seminar for history graduate students. The following year, we ran a graduate seminar in Historiography and Historical Thought. Then, the next year and the one after, we taught the Finishing the Thesis seminar together. Occasionally, Thomas also ran ad hoc professionalisation seminars for our postgrad students. I watched him in these classes and got to know him well. He was ever whip-smart and inspiring. He enjoyed teaching students—and it showed.

Did Thomas ever seem a bit distracted or frazzled when you ran into him in the hallways? He had plenty on his mind. Let me note a few of the other activities that he was doing for us over those years.

For 2016 and 2017, he worked with me as the History postgraduate coordinator—back then, the largest service role in the department. But, at the same time, he held the position of the Academic Director of the USSC. This is a massive role, equivalent to being department chair, encompassing negotiating staffing contracts, helping set curriculum, and dealing with various issues related to the financing of the Center.

At the same time, he was supervisor or associate supervisor or 5 postgraduate students—most of whom have now finished or are about to do so.

Each year of his tenure here, he also gave a large public lecture. And practically every week he was on radio or TV, discussing American politics (he actually made more than 100 TV and radio appearances in the first 4 years of his work here). At the same time, he was writing for important online fora—including the New Matilda, Jacobin, ABC Online, the Huffington Post, the Australian, CommonDreams, and more.

He was, of course, engaged in academic writing as well—on a book, The Servicing of America: Work and Inequality in the Modern US; an edited collection, Remaking New Orleans: Beyond Exceptionalism and Authenticity, which came out with Duke in 2019, and a range of special issues, book chapters, and articles—15 of these published between 2014 and 2019 to be precise.

From a purely selfish perspective, one of my favourite things that Thomas did while he was here was to connect Americanists in the Southern hemisphere in a way we hadn’t been connected before. Along with Sarah Gleeson-White in the English Department, he applied for a major grant through the Faculty Collaborative Research Scheme, to create the American Cultures Workshop. They located everyone working on any aspect of America, set up a monthly seminar series, and paid to have speakers present work-in-progress. This ran (under new leadership) until the pandemic hit, and it was an unprecedented success. It was particularly helpful, I think, in providing opportunities for our postgraduate students—to give papers; to meet others in the field; to make new colleagues and friends.

Thomas is an enormous loss to the University of Sydney. I will miss Thomas because he was always interesting to talk to. He truly cared for our students. He’s a gadfly—willing to provoke the powers that be. Unsurprisingly, he inspired then. He’s an iconoclast—never just mouthing the latest theories (although he knows them all). He thinks for himself. He’s not just thoughtful, but also irreverent, funny, and warm. We swapped as many cat memes as we did teaching ideas or thoughts about history. He taught me a great deal while he was here, and although I know we’ll stay connected, it won’t be the same.

I’ll add that it is totally typical of Thomas to show up and give a brilliant paper in the immediate aftermath of a devastating hurricane, while looking like he’s doing nothing out of the ordinary. And it’s equally typical for this paper to be about the public and political function of history—on a project that drew in our students and helped them to see what difference history can make in the world beyond the University. This paper spoke more eloquently than anything else of exactly what we’re losing—a remarkable intellect, an engaged teacher, and a wonderful colleague.

The Department of History wishes Thomas all the best in his (many) future endeavours.