Before I started the HSTY3902 unit, when I thought about public history I often discounted its validity because I believed museums and other historical spaces only showed the public the stories/images of the past they desired to remember or commemorate. However, one particular reading from the unit has managed to change my perspective. Thomas Cauvin’s article ‘Shared Authority’ highlights that public history has the possibility to be more than just an arena to unquestionably celebrate/commemorate victories and tragedies. In Cauvin’s article I like the idea that “…historians should strive to understand [the past] as it really was, not as what people want it to be, and by doing so should endeavour to create a space for discussion about the past”.

As many are aware, there are multiple perspectives and interpretations of the past and each need to be heard, discussed and analysed in order to create a truer picture of history. Only by allowing public audiences to see and hear multiple voices, including those which juxtapose to their own experiences or views, can there ever be a ‘shared authority’ of the past between historians and different groups and individuals of the public. If only one story is ever told from a singular point of view, it can ever only feel owned from a small fragment of society.

1 Step Forward 2 Steps Back: It’s all history!

You don’t always know where you’re going, what you’re looking for or what you’ll end up with, but even more so, it’s sometimes hard to stop looking! It’s an exhilarating, ironically non linear ‘choose your own’ adventure where anything could happen, so many tracks to go down. You go on tangents and find things you never expected to, or wild goose chases where nothing turns up. Sometimes records are missing or literally eaten by rats, or a perhaps a paper shortage! But how fabulous is that! The gaps keep you coming back, it’s a thirst for the whole picture. You get to know the ‘characters’, imagine their lives, feel a strange connection and a sense of responsibility to finish what you started. I am doing a history of ordinary people, who lived in a ordinary house, but ordinary for me is what makes this type of history so exciting. Anyone can become history and anyone can find it. History is part of family life, the community, the future.

(Certificate of Title: Henry Wardrope 1910 Vol 2102 Fol 117 http://images.maps.nsw.gov.au/pixel.htm )

Mr and Mrs Wardrope are my centre point from which my study spreads. This project spawned from an enquiry from their ancestor, their beautiful sepia portrait and their house between the old Town Hall and Blue Mountains Echo (later ‘Daily ‘paper). I still do not know the end result, but the experience has been invaluable. I feel attached to their story, even if it is not exceptional it serves as an insight to the lives of migrants, the experience of family and work in the early 20th century, the township of Katoomba and the legacy members make serving the community.

It is also an interesting look at the evolving urban environment. Still seen to be as a large Township, Katoomba has grown from a mining town, a touristic centre, a medical escape to a vibrant multicultural hub for all types of people and business still serving some of the functions it once did. A study of this property, the changing size and shape it took over time, the amalgamation, transformation and destruction serves as a larger analysis of the growth of settlements and urban expansion. Further, it is interesting to understand how history meets heritage and how a study of the people and places are key to preserving aspects of the past for our future. And while a car park stands there now and much of Katoomba has been reshaped since its earliest developments, respect of the past lived experience is crucial, even starting from the smallest house squeezed between two key buildings.

As I do not wish to give too much of the story away, I will leave you here, hopefully keen to learn more about the voyage of the Wardropes across the world to the unknown, settling in the inner west before finding their community in the Blue Mountains, about the agricultural to urban evolution from the first land grant to the car park for Civic video which stands there today. Local, small scale history is important as it is relatable, it as an unseen aspect of our past and past community members which have contributed to our lives today.

A change of plans …

I remember hearing from other students from last year’s class speaking about how they chose their final project structure at the last minute, or changed their idea just in time to stress out completely. A common theme among them, though, was how proud they were of their final product.

As I heard these recounts, I thought (a little too smugly) that that was nice, but it didn’t apply to me and my organisational genius. I had picked out my organisation, I had organised a position and started volunteering every Friday at the library, and I was gathering research for a walking tour. I was set.

I didn’t account for the role that genuine interest plays in the history making process, or at least in the academic sphere. To be clear, I certainly did not dread my original project idea (which was to create an informative blog around the ‘Crime in Vaucluse’ walking tour that the Woollahra Library will give sometime in December), yet something was bugging me. I remember the multiple encouragements that Mike gave us that were along the lines of: make use of your skills, experiment with different modes of communication, and strangely enough… have fun with it! (I’m sorry, what?)

And for me personally, this is the act of writing. Without going into depths about my hopeful future in this practice, it is what I am drawn to again and again. I mentioned in my last blog about the difficulties I was facing in terms of imagining the human qualities and character behind Sir Henry Hayes (an Irish convict who set up Vaucluse House). I dove further into this interest, and narrowed my research to feature just Sir Henry. It seemed the more that I delved into his past, the more fascinated I was by the character he must have been. To lay out a few facts from the research I have gathered using the Woollahra Library Local History resources:

-Sir Henry Hayes was a Sheriff in Cork, who came from a wealthy manufacturing company. Around 1795, he became a widow with 7 children.

-Hayes abducted Mary Pike, a wealthy heiress. He showed little remorse of this act, and Mary Pike fled to England with her reputation in ruins.

-Hayes eventually turned himself in after two years on the run. Why did he do it? This question has been bugging me an insane amount!

– He paid for the best room money could by on board the Atlas, the convict ship heading for NSW.

– Immediately he showed a distaste for authority, becoming enemies with Governor King, and constantly being sent to other parts of the colony under suspicion of organising uprisings against English rule.

-He tried and failed (and tried again) to set up Australia’s first Freemason House and it is rumoured that he hosted the first legitimate Saint Patrick’s Day celebration at his home, Vaucluse House.

The list goes on, but most importantly I want to portray these facts (that are so often condensed to dates and places) to a wider audience that might be interested in this man through a different mode- that of narrative history.

I plan to create some diary entries with the first-person perspective of Sir Henry Hayes and post them to a blog site of my creation. Crucially, I will be basing all the facts upon historical evidence, and I will have links to the various primary or secondary sources that I have used to create the story. In this way, I plan to bring a different mode of interest to the biography of such an interesting character.

At the end of the day, I want people to possibly stumble across this account of Sir Henry and be intrigued enough to read on, to read the primary sources or visit the Vaucluse House. I have offered Woollahra Library the opportunity to draw attention to the project if they feel that it will increase interest in the historic site, and the historic man.

At the moment I am in the process of writing up the diary entries and putting them on the website. I have learnt so much during this process- from working out how to set out a website, to thinking about the best way to produce content in an original yet educational manner. I am swiftly realising that the balance between entertainment and historical education is a fine one, but I am enjoying having the freedom to choose how I want to present the story of this man.

I certainly didn’t take into account how long the research period would be. Thankfully the Woollahra Local History department had many wonderful, hard-cover books that gave me the majority of my information. This was good news too, as most of the scarce information on Sir Henry Hayes on the internet is either far too vague, or written by historically-minded writers who haven’t shown any evidence for their claims. Then came the time consuming task of writing these quotes up in a Word document, so that eventually I can paste quotes onto the site (with full referencing, obviously). This is all to ensure that I can say that a large portion of my work has been based on historical facts mentioned by previous publications.

Regardless of this work, it has been such an immersive and challenging experience that already is giving me a sense of pride in what has been made so far. I plan to continue this work after I hand in what I have written so far, because I am realising now that I will not be able to write all the diaries entries that sum up the long Convict-Career of Sir Henry Hayes. I suppose I fell into the trap of thinking I could do more than was realistic. Regardless, I still have a week(ish) until I have to hand in my project, so I hope to keep writing up until that point. I hope the end product reflects the time and effort I have put into it. All in all, I have learnt some genuine skills through this project, and it has been a rewarding task to try and create something that both meets the academic interests of my course, but also engages me as a writer and historian.

Breaking through the noise

The semester had come to close and I have turned my focus from researching to presenting. I will be submitting two projects – a website and a video. Originally I intended to submit just the website, but after seeing the end product I decided it wasn’t original or creative enough. Don’t get me wrong, I think the website looks beautiful and serves the purpose of highlighting the fascinating lives of the old girls whom I researched and I hope the KOGU community will find it useful, but it wasn’t enough. So I decided to create a video. A video which isn’t really a documentary isn’t really a movie and isn’t an interview. I am not sure what to classify this video as, but I hope that will be the strength of it. I tried to create something that was a little unusual and different and I hope I have succeeded.

One of the major reasons I wanted to create something different is because I have found through my study of history, ancient and modern than the unusual and more original stories and presentation formats are often the ones most remembered. Today is the 11th of November – Remembrance Day. My knowledge of World War I is not great but there is one story which I love – the Christmas Truce story. The story goes that on Christmas Day 1914 the British and German troops on the Western Front called a cease fire for the day and played football in no-mans land. To be honest, I am not entirely sure that the story is true, but I think it is (or at least hope it is). Now I think the reason this story is so well known is because it is different and unique. In the constant history of war and hatred and opposition this one story of peace and kindness shines through. Throughout history there are many well-known anecdotes or stories that have been remembered and passed down and I think we have to ask ourselves why these stories are remembered and captivating whilst others are not. I think stories like these are especially important in local or community history because they have the ability to infect people’s brains and be transmitted and become alive. Stories which are alive and captivating are so important in local history when the historian is always struggling against the tide of people interested in wars or revolutions and not the local swimming pool. I hope that my story and my presentation method can act like this and cut through to the people who will appreciate it the most.

But what did you learn?

As this session comes to a close, reflecting on what I have learned through this course seems like an appropriate idea to write about. The themes I think of when reflecting on this course are the concepts of public history, local research and community engagement. These three things are completely new to me and highlight just how much there is for me to learn at university and through history. Through learning these things this session, it expanded my outlook of my local and university community.

This learning experience has highlighted indigenous, local and community histories that I otherwise would not have known about. The stories and tales found through local research highlighted the need for public history and community engagement. A story that stands out to me is one of Alexander Berry (one of the founders of the town) who collected and exhibited indigenous skulls, both in Australia and Scotland. Through local research I found this story, through community engagement, I discovered the context of Alexander Berry, and through an analysis of public history, I was able to find a way to mold it into my work.

The recount of Alexander Berry’s actions highlighted to me how discovering things through local research it is both interesting and relevant. The context and background that this gives to the history of the David Berry Hospital. I found a small detail can provide a context to the family and community. Through engaging with these themes, I found meaning in all we have learned this session and find I am much better able to negotiate all the information found during community engagement.

Tomayto, Tomahto; Frenchs Forest, Forestville.

Historians are indoctrinated with the importance of dates and names from an early age. I can certainly still regurgitate the dates of significance from WWI and WWII along with names of high profile Nazi party members on demand (thank you very much HSC Modern History). For the majority of my undergraduate degree, most of my historical inquiry for essays and assessments has largely been sourced from secondary sources. So its unsurprising that it is now, when I have very little secondary sources to draw upon (except for the Local Studies gold mine at Dee Why Library) that I’m discovering just how difficult it often is making sense of the past.

My major project will take the form of ten blog posts about lesser known histories of the Northern Beaches. I came across the mention of Forestville Soldier’s Settlement in my early research, immediately intrigued, and jotted it down as a topic for one such blog post. Little did I know that this would be the beginning of a very frustrating search for further information.

Inputting this exact name into Trove and Google returned very few results;

![]()

My hopes of finally stumbling across a piece of Northern Beaches history that could be told in a fascinating narrative were slowly withering away. However, I’ve never been one to back down from a challenge – so I started thinking and searching laterally. Thankfully, by skimming the similar results that Google provided, I gained my first clue. Forestville and Frenchs Forest appear to be used interchangeably in different excerpts.

For those unfamiliar with the beautiful bushland suburbs north of The Bridge, Forestville and Frenchs Forest are two adjoining, but different, suburbs. This clearly hasn’t always been the case. James French was the first to settle most of this area and developed a timber industry, explaining ‘Frenchs Forest’. However, the soldiers’ settlement (an Australia-wide government initiative to provide farmland and, subsequently, livelihoods to soldiers’ returning from WWI) was actually within modern Forestville.

Given that I had now determined this particular soldiers’ settlement was located in Forestville, but potentially referred to as Frenchs Forest – I entered this into Trove and Google, crossed my fingers, and hit enter.

JACKPOT. Not only did this bring up a wealth of sources to work with (even an entire book on the subject written by a local historian!), there was some juicy details involved. The land in this area was largely infertile, and the returned soldier’s felt particularly failed by the scheme – so they launched an inquiry that was bountifully covered by local and national newspapers.

Shakespeare’s Romeo so famously asks; ‘What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet”. Well, he has a very valid point – tomayto, tomahto; Forestville Soldier’s Settlement, Frenchs Forest Soldier’s Settlement – different names for the same thing.

(Side note: the soldiers’ settlement scheme is itself very interesting and deserves an entire blog post or essay itself).

“Save Cemetery for the Nation” – An urgent call to preserve Australian history

“Vandalism”. “Disgraceful Condition”. “Apple of Discord”. “Neglected Dead”. “Vaults in Ruins”. “A City’s Disgrace”. These are just some of the phrases used over the decades in news headings to talk about Saint John’s Cemetery in Parramatta. From as early as 1868, newspapers were calling attention to threats on the cemetery, with accusations ranging from vandalism to neglect. For over a century, the call to take action, to remember their heritage and to look after the final resting place of some of Australia’s earliest European settlers has been spoken among Parramatta locals. For this cemetery ‘is an immensely significant site…due to its links to the history of the British Empire and world convict history’ (http://stjohnscemetery.jimdo.com/about-1/).

I began looking into the history of Saint John’s Cemetery in the media after receiving a news clipping from a fellow historical student (who now has her own unique, historical blog at https://lonelybeaches.wordpress.com/) titled “Save cemetery for the nation”. Written in August of 1970, this article depicts a pretty sad and beaten picture of the cemetery’s condition. ‘Whisky and rum bottles…lay in a tomb which had been attacked by vandals’ and ‘tangled weeds and blackberries hide some of the graves’. The article speaks of an appeal made by Bishop H. G. Begbie, the Bishop in Parramatta, to restore the cemetery. This appeal was supported by the cemetery Trust as well as members of the Parramatta Trust. The hope was for descendants of the people buried in Saint John’s cemetery to take action in the restoration and to add weight towards an appeal to the Federal and State governments, as well as to the Parramatta City Council, for annual grants for maintenance.

As suggested above, this call was not a new endeavour. The earliest mention of the state of the cemetery presented on the Saint John’s Cemetery website (http://stjohnscemetery.jimdo.com/media/) speaks of vandalism that had hit a number of churchyards, including Saint John’s Cemetery. This news clipping from 1868 spoke of youths plucking ‘flowers planted by bereaved relatives and friends’ and warned that ‘the perpetrators of such wanton outrages were liable by law to severe punishment’. The aim of this notice was to caution these youths of the consequences of such acts and hoped it would be enough to deter any subsequent vandalism. As the decades passed, Saint John’s Cemetery was described as being ‘in disgraceful condition’ and ‘so unsatisfactory as to give rise to much regret’, as well as being, ‘to a large degree, in all stages of neglect and decay’. Comments such as these continued to be issues worthy of news space up until 2015 (see Clarissa Bye’s article “Historic St John’s Cemetery at Parramatta in state of neglect”).

The site has finally taken a turn in recent months, however, as the Friends of Saint John’s Cemetery work alongside Parramatta locals to restore and preserve what is left of this history. Recent events have worked to spark new interest in the cemetery, especially among the local community. Lots of work has been and continues to be done. And it is paying off; the cemetery is now quite pleasant to visit. Restoration is not enough however, and the need for funding and the proper telling of its history continues to be a prominent issue. The Saint John’s Project is working to give voice to the numerous stories of those buried in the cemetery. New medians such as Facebook, Twitter etc., are used to call for helping hands and funding, but the call remains the same as what was displayed in newspapers all those years ago: “save the cemetery”.

What draws me to the issue of keeping some old cemetery tidy and presentable is the bigger issue that Australia has with its neglected history. A few years ago, I took a trip around Europe. I visited fourteen cities and towns in nine different countries and was overwhelmed by the amount of history that stood, plain as day, in every street. Everything from old buildings to tucked away museums to cobblestone roads, Europe’s vast and rich history is out in the open for anyone to see. While thousands of people travel to Europe every year to see its historical sites, few people realise how much Australia has to offer in this very department. There are more “plain as day” sites in Australia than even I realised until very recently.

Much of this is simply because Australia, and especially its government, is not taking advantage of its historical resources. Sites like Saint John’s Cemetery would easily be popular tourist sites in a place like Europe, yet here in Australia, its often left unknown to tourist and Australians alike. It is a living testament to some of Australia’s earliest European history and can be quite a sight to behold on a sunny spring day. Walking distance from Parramatta’s historic Female Factory (yet another neglected historical site) and the Old Government House, the cemetery ‘is one of the jewels in Parramatta’s heritage crown’ and sits in a rich, historical area (http://stjohnscemetery.jimdo.com/about-1/). With the right resources, such as access to walking tours, good historical maps, clear signage and descriptions, etc., this area could achieve a very similar experience to walking through some of the old towns in Europe. The call to “save the cemetery” is not just a call for local Parramattans, but should be a call to Australians everywhere to save the history of this nation.

‘People power’ of booze and music.

It has been difficult to try and argue that Sydney’s Inner west music and pub culture is historically relevant to an audience that does not necessarily recognise that attending pub gigs is culturally powerful. Perhaps it was arrogant of me to think that the community I socialise within is as captivating as I believe it to be, historical or otherwise. Everyone sort of already knows that music is an important aspect of life – the number of people walking around with headphones in attests to this. Though is it really worth historically investigating? I doubt my contact seems to think so either… he loves what he does and thrives on it, but that satisfaction does not seem to encourage greater investigative curiosity. One thing is for sure, a study on music and booze does not par with some of the more noble community causes that my peers are engaging with. It is stressful that this is what I am thinking at this stage of the project.

I blame the inextricability of music for my project’s current limbo state. Music is so connected to the experience of being human, played whenever people gather. Its accessibility means that people likely don’t think about its cultural role beyond entertainment. It operates or ‘plays’ in a free space, autonomous from politics or other rules, but is reflexively influenced by them as well. It has also been expressed that music has influenced the course of history through mobilising people power. Rodriguez, Bob Dylan, Bob Marley and Midnight Oil immediately come to mind. So yes, music is arguably historically relevant, but Australian pubs and drinking culture? I’m yet to articulate how.

[Sorry! The image is too large to embed]

At first look, the archives I have accessed seem to further trivialise music and booze to only have entertainment and business value. The drum ads collated by a colleague of the Rule Brothers in tribute to their work at the Annandale Hotel undoubtedly holds sentimental value, but they require a historical perspective – mine – to apply the advertisements to a broader cultural context and argue that they evidence Australia’s cultural development. While myself and the Rule Brothers confidently argue that pubs are communal spaces where ‘people power’ can be unleashed, it is difficult to find clear evidence. I can only think of Keep Sydney Open as an obvious example of this.

The fact that I could spot some familiar musical names amongst the drum ad collection ensured me that this project was personally significant: I want to prove to my audience that the two very separate worlds of history and music and booze can collide. This project presents an opportunity for me to defend my interest in history to those who perhaps are distracted by the performance factor of music.

Parramatta High School visit

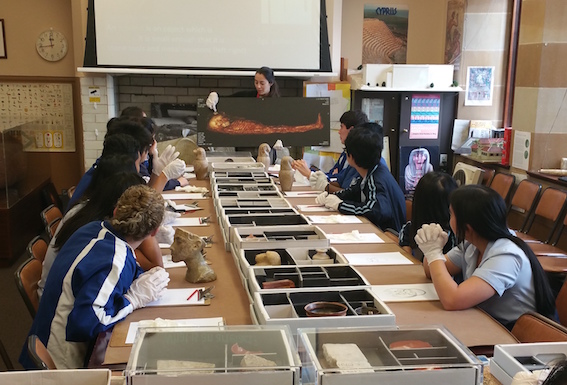

Parramatta students handling artefacts from the Nicholson Museum

Just as they were submitting their subject preferences for years eleven and twelve, Year 10 students from Parramatta High School visited the University of Sydney in September to learn more about studying History. Associate Professor Michael McDonnell, along with Dr Elly Cowan and Professor Chris Hilliard, greeted the students and introduced them to the expansive range of topics that fall under a history degree, and the potential career options opened up by studying history at university.

A hands-on artefact session with the Nicholson Museum followed, and as the class examined a range of Ancient Egyptian artefacts, it soon became clear that we had an expert among us. Turns out one of the students could remember precise details about Ancient Egyptian funerary artefacts from a school project she had completed in Year 4. With a memory like that, she is well-placed for a career in archaeology.

Afterwards, the students were introduced to the main exhibit of Nicholson Museum by Dr Jelle Stoop of the Classics and Ancient History Department. This was followed by a campus tour led by USYD volunteers Emma Cleary, Anastasia Pavlovic, and Minerva Inwald. As they learned about and saw more of the campus, many of the students opened up a stream of questions on university life – about studying anything between journalism and music, about making friends and getting involved in social justice on campus. Others expressed uncertainty at making decisions about their futures – which, of course, is pretty normal, and there are few places better than university to embrace and explore that uncertainty.

Sexxx Laws: Decriminalisation in NSW

In all of their literature, Touching Base repeatedly accredit their success, as both an organisation and an advocate, to the decriminalisation of the NSW’s sex industry. It allows them to operate and to campaign openly freely the rights of both those with disabilities and sex workers. With that in mind, I thought I’d look into the laws of our state and the history of how we came to be so damn progressive.

Sex work is regulated by state government and as such the laws differ from state to state. NSW decriminalised the sex industry in 1995, an incredibly progressive move for any state. Decriminalisation allows the best options for sex workers in terms of their own health, safety, and personal agency. However, decriminalisation was not designed with their best interests in mind. The laws were based on the Wood Royal Commission of 1994-1997, or as I previously knew it to be – Underbelly: The Golden Mile.

Australia has a long history of police corruption in prostitution; one I imagine is not specific to our country alone. Sandra Egger’s research into the early days of the colony has found a history of payments to police to keep brothels operating. This I’m sure is not surprising, the two seem to go hand in hand. Egger highlights the early 1960s to 79 as the ‘high point for police corruption.’ Coincidentally from 1968 to 1979, NSW’s laws were the most restrictive they had or have ever been. Payments to the police were seen as an operating cost for sex workers and brothel owners. This ‘mentality’ (read corruption) naturally carried over into the 1980s and 90s and what better area for it to flourish than Kings Cross. The Wood Royal Commission was instigated after claims of a paedophile network making payments to police to avoid arrest. These stories dominated the press and even looking back now they are hard to read. The Wood Commission would go on to acknowledged a widespread endemic of corruption throughout jurisdictions, but in no precinct was it as concentrated and as prolific as in Sydney’s notorious Kings Cross. A day in the Kings Cross precinct was described in SMH by a former officer:

The hours of duty for a detective on the day shift were between 8.30am and 5pm…Morning coffee commenced about 9am and continued until about 11.30am, whereupon there was a discussion about a suitable luncheon venue, which lasted until about 12.15, then lunch commenced and usually concluded about 3.30pm. It was followed by an ale or dozen at the infamous Macleay Street drinking establishment, the Bourbon and Beefsteak.

Honestly, why wouldn’t you want to be a cop? You just get to hang out with your mates and drink all day! In order to avoid jail time however one of these cops, Trevor Haken, ‘rolled over’ as they say, which was a pretty big get for the Commission. Haken’s car was fitted out with surveillance in which he captured evidence of senior detectives accepting bribes. Haken’s evidence was crucial in spurring the Commission on, a Commission which attacked all sides of the force in an attempt to break down the code of silence which prevailed. The Wood Commission found evidence of:

process corruption; gratuities and improper associations; substance abuse; fraudulent practices; assaults and abuse of police powers; prosecution— compromise or favourable treatment; theft and extortion; protection of the drug trade; protection of club and vice operators; protection of gaming and betting interests; drug trafficking; interference with internal investigations, and the code of silence; and other circumstances suggestive of corruption.

This is summed up in the catchphrase of the report: a ‘state of systemic and entrenched corruption’. Why is this interesting in relation to sex worker laws? When I first started reading about sex laws in NSW I looked at gender studies and sexual citizenship, I assumed it was something couched in the shifting political scene and second wave feminism and indeed there is an argument to this. But essentially the progressive laws that sex workers are so proud of here in NSW were not made with their best interests in mind. They were made to limit further possibilities of corruption within the police force. If prostitution is legal then it reduces the opportunity for officers to accept and enforce a ‘taxing’ system.

In 2015, the state government flirted with the idea of a new licensing system for the sex industry. The system would have appointed the police as regulators of the industry, a scary proposal for those who can remember the 90s and/or what happened on Underbelly. Touching Base, The Scarlet Alliance and Sex Workers Outreach Program (SWOP) fought this hard. They argued that the threat of regulation would result in brothels and workers heading underground, making health and education services harder to access. It would also jeopardise the safety of workers by shifting the nature of their relationship to the police, they would no longer feel safe to seek police assistance in times of need. And it would, of course, increase the opportunity for corruption. In May 2016 the government elected against the licensing system in NSW, reasoning that the proposal would incentivise non-compliance and would be of high cost to the government themselves.

NB: I have the utmost respect for the police and sex workers alike. I think they’re both great! And this is in no way an extensive review of the Wood Royal Commission which is in and of itself fascinating. This post could have gone on for days. I recommend having a google of it if you’re that way inclined.