Professor Kirsten McKenzie was elected a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities.

Dr. Miranda Johnson weighed in on the Australia Day debate by talking about the ongoing legacy of settler-colonialism with the international online magazine, OZY.

ARC Research Fellow Ben Silverstein won the History Australia and Taylor & Francis best article for 2017.

PhD students Hollie Pich and Marama Whyte have both won Endeavour Awards to undertake research in the U.S. in 2018. These highly-competitive awards are provided by the Australian government to scholars engaging in study, research, or professional development overseas. Marama has been granted the Endeavour Postgraduate Scholarship to conduct 6-12 months of research at New York University, sponsored by Professor Thomas Sugrue, while Hollie has won an Endeavour Research Fellowship to conduct 4-6 months of research at Duke University, sponsored by Professor William Chafe.

Marama Whyte has also won the Tempe Mann Travelling Scholarship for 2018, which is awarded by the Australian Federation of Graduate Women-New South Wales, taking up an honour that Hollie held the year before.

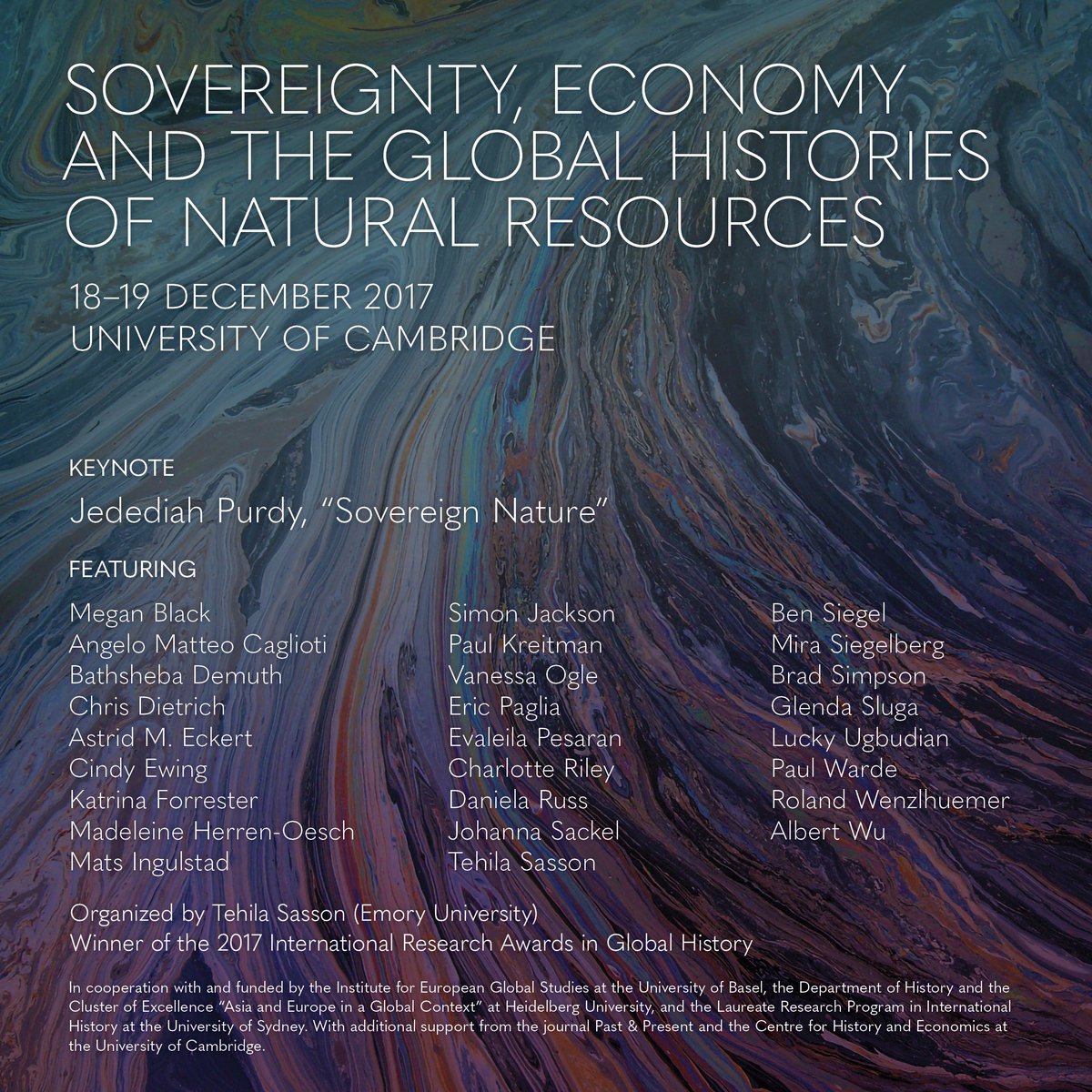

Professor Glenda Sluga recently presented at the Graduate Institute Geneva on the history of global governance of the environment. For the Geneva report on this talk click here. Glenda is also cosponsor of this Cambridge conference on the global history of sovereignty and natural resources. This was the winning concept in an international competition. A copy of the poster is available here, and you can download the final program here. The Guardian also reported academics from around the world including Professor John Keane from the Department of Government and International Relations and Professor Glenda Sluga from the Department of History are rallying in support of Dr Maha Abdelrahman, a Cambridge University scholar whose PhD student Giulio Regeni was murdered in Egypt.

The New Republic (US) discussed Dr Chin Jou’s new book, Supersizing Urban America about fast food and obesity, and she was interviewed by KPFA Radio (US) about it. Dr. Jou also wrote a piece on the global expansion of the fast food industry in the Washington Post.

University of Sydney PhD student Emma Kluge has a new piece on the UN History website on Decolonization Interrupted: U.N. and Indonesian Flags Raised in West Papua

Channel 7 (Sydney, Perth, Melbourne, Brisbane) interviewed Dr Miranda Johnson from the Department of History about broadcaster Stan Grant’s calls to change a statue of Captain Cook in Hyde Park.

Dr. Marco Duranti’s The Conservative Human Rights Revolution and Prof Mark McKenna’s From the Edge were longlisted and shortlisted respectively for the CHASS Australia Book Prize 2017.

Dr. Duranti was also interviewed on ABC Radio National about the human rights revolution born in a conservative UK after World War II.

Dr Sophie Loy-Wilson was interviewed on ABC Radio National about Australian migration to China and the story of Daisy Kwok, a Chinese-Australian socialite who was born in Sydney and moved to China in 1917.

Dr. Ivan Crozier and Dr. Peter Hobbins have both spoken recently in the University of Sydney Rare Books ‘Rare Bites’ series of lunchtime talks, which they video, caption and upload to YouTube: Peter Hobbins speaks on Researches on Australian Venoms (1906); Ivan Crozier speaks on Sexual Inversion (1897), and Dr. Hobbins featured on an episode of ABC TV’s Hard Quiz, and co-authored an article published on The Conversation about misconceptions around the fatality risks of snakebites.

Professor Dirk Moses recently wrote about the pros and cons of “flipping” the classroom in a large first year unit in Teaching@Sydney.

Professor Sheila Fitzpatrick authored an article published in the Australian Financial Review about the 100 years since the Russian Revolution, and she was interviewed by ABC Radio Melbourne about her new book, Misckha’s War.

Professor Mark McKenna from the Department of History was quoted in the Daily Telegraph about Australia’s historical monuments, and he also wrote a review of Donald Horne: Selected Writings, published in the Weekend Australian.

Sky News interviewed Professor James Curran from the Department of History about US President Donald Trump’s reaction to the events in Charlottesville and was interviewed on ABC Radio Sydney, 2SM Sydney and Sky News about the history of the ANZUS alliance in light of the Prime Minister confirming Australia would join US military action if North Korea were to attack. Professor Curran also wrote an article about what the ANZUS treaty obliges, published in the Australian Financial Review, and another in the Australian Financial Times about Australia’s ongoing alliance with the US during the Trump presidency. Weekend Australia published an article by Professor James Curran from the Department of History and the United States Studies Centre about how US President Donald Trump has intensified the cultural crisis gripping the US. CNN (US) quoted Professor James Curran from the Department of History and the United States Studies Centre about the federal government’s foreign policy white paper. The Saturday Paper quoted Professor James Curran about the Foreign Minister’s relationship with US diplomats. The Straits Times (Singapore) quoted James Curran about the resurrection of the quadrilateral security dialogue between the US, Japan, Australia and India.

The Star Tribune (US) quoted Professor Robert Aldrich from the Department of History about his research on French colonialism, while the National Post (Canada) quoted him in a story about increased attendance at the National Museum of the History of Immigration in Paris following the 2015 terrorist attacks in France.

Professor Ian McCalman from the Department of History and Co-Director of the Sydney Environment Institute was interviewed on ABC Radio National’s Conversations with Richard Fidler.

9news.com.au quoted Emeritus Professor Richard Waterhouse from the Department of History about Remembrance Day.

Professor Shane White from the Department of History published a review of The Origin of Others by Toni Morrison in the Sydney Morning Herald. The review was syndicated across Fairfax Media.

ABC Radio National interviewed Professor Sheila Fitzpatrick from the Department of History about the Bolshevik revolution.

Dr Thomas Adams featured on ABC’s The Drum discussing a number of topics including the Manhattan terrorist attack and US President Trump’s comments following the event.

Category: Department News and Events

Scandals and Historical Curiosity

In this blog entry, Professor Kirsten McKenzie reflects on the utility of studying historic scandals. Her thoughts are drawn from the presentation she gave at a plenary session on Historical Curiosity at the recent History Postgrad Conference, “The Past and the Curious” in November 2017.

Historical Curiosity

I’ve taken inspiration from the theme of this conference in two ways – firstly, what use can we make of curious incidents in the past? And, secondly, how do we deal with our own curiosity about them?

I’m still not entirely sure whether this is by accident or design but I’ve come to realise that much of what I research can be classed as ‘curious’. I don’t mean in the sense that the past is another country, and what might seem odd to us was not so previously. These are events and personalities who were considered downright weird at the time. My two most recent books are both about convict impostors in the first half of the nineteenth century, although their impersonations were undertaken with very different motivations and effects.

One, the improbably named John Dow, was a con artist seeking gain through identity theft. The other, who began his life as Alexander Kaye and ended it as William Edwards, was an escapee trying to hide under a false name. Both got caught. Neither would admit their guilt. In the case of Edwards the mystery persisted even after the prisoner took his own life. These cases excited much curiosity and debate in their own time, even if they were largely forgotten afterwards. When remembered, they were never considered the proper subjects of serious history.

By their very nature, Dow and Edwards were serial liars. Their actions confounded observers at the time, several of whom described them as insane. Much of their story remains unknowable. This brings me to my second point – what do we do, as historians, with our curiosity about the past. How should we direct that curiosity?

When I was sitting where you are now – and in the last year of my PhD – I gave a presentation at a large international conference where the papers were pre-circulated and where Ann Stoler was the keynote speaker. For those not in my field, Ann Stoler is one of the big names in imperial history, and was already an academic superstar in the late 1990s. So, you can imagine how I felt when mine was the paper she singled out for praise and discussion as part of her keynote address.

When I had found the material on which the paper was based, I knew it was a huge coup – I was writing a thesis about questions of gender and honour and I had found a cache of papers about alleged incest and concealed pregnancy involving the Chief Justice of the Cape Colony, Sir John Wylde, and his daughter Jane. The day I came upon the papers saw me quite literally shouting aloud with joy in the car all the way home from the archive. Which seems a bit sick when you consider the contents of the material itself.

But this wasn’t why Stoler singled out my paper for praise – she admired what she called (and I can still remember the gist 20 years later) my ‘postmodern determination’ not to become caught up in the solution to the story, but rather to leave the mystery unresolved. Instead of putting what had happened to Jane Elizabeth at the center of my analysis – was she the victim of rape or incest? had she killed her own child? had she had a lover whom it was somehow impossible to acknowledge? – I had focused in the paper on the wider significance of the scandal for understanding Cape colonial society – how it related to debates over slave emancipation, the press, and the nature of gendered discourse in public and private.

My immediate thought when I heard Stoler’s comment on my paper was – ‘well, I’m glad this great scholar thinks I have postmodern determination, I better start pretending I’ve GOT postmodern determination because the reality is that if I could have solved the mystery from the sources available I would gleefully have done so.’

I mention this as a foundation story in my career not only because it pointed the way to the historian I would become – one who specialised in scandal – but also because it took the process of writing several books to work through quite how incisive Stoler’s comment was to how we should approach the phenomenon of scandal. Indeed, she likely didn’t realise herself the significance of what in retrospect was probably just an off-hand remark.

If historians want to understand the kind of everyday attitudes that are the focus of cultural history, why work on scandals? They are surely unusual events by definition? But, of course, some people are scandalous, only if others are not. So, they allow us to see where the lines of acceptable and unacceptable behaviour are drawn and constantly renegotiated.

Secondly, they generate extensive sources and articulate what are often unspoken assumptions about proper behaviour. Scandals can also have important effects in bringing about social change – they can involve the rise and fall of public figures, they can have concrete political effects by bringing unacceptable behaviour under public scrutiny. They can be used by the powerless to shame and expose the powerful. They can be used as political traction to bring about desired outcomes, often only peripherally related to the original scandal itself. All of this is inherently unstable and unpredictable – scandals are extremely difficult to manipulate. They often start out as being about one thing or person and end up being about something quite different. The scandal of John Wylde and his daughter is a textbook example of this.

For all these advantages, the historian of scandal must be prepared to have her curiosity frustrated. She must always face the prospect of suffering what the novelist A.S. Byatt calls ‘narrative greed’ – and of accepting that this greed will not be satisfied. This is not to say that narrative is a bad thing – but it isn’t the only thing. There is always the search for the good story when writing about scandal, the satisfaction of finding out ‘what happened’, of marshalling all the twists and turns of plots and sub-plots.

It is notable how often historians of scandal use the language of plots, or of drama when they are setting the scene. We need to be honest about the narrative pleasures of this sensationalism. There are very good reasons why we might want to know what happened. But as I tell my students in the unit ‘Sex and Scandal’, some really bad history – often for general audiences – can be written about scandals in the name of telling stories. This risks not only being bad quality, but having bad effects, simply interested in the prurient details, details that are taken for granted and sensationalized, with no attempt to understand what it all means.

It is worth mentioning that I found the Wylde material (marked as “under restricted access”) with the help of a very experienced archivist – and he said quite explicitly that he had only brought it to my attention because he knew my scholarship and he was satisfied that I would deal with it responsibly. (I’m glad he didn’t see me shouting in the car on the way home.) Our curiosity is natural, and important in getting things right, but it is important not to become caught up in a historian-as-detective approach when dealing with scandal. This is not CSI Archive. Sometimes the best solution is to set aside one’s natural curiosity to discover a secret – or to become curious about something else.

Let me end with an example of this from my most recent book. One of the most challenging parts of writing Imperial Underworld was addressing an incident in the life of William Edwards that has been written about numerous times – but never in a scholarly way. This involved a notorious scandal that was intensively investigated at the time – without a satisfactory solution. An anonymous placard was posted on the streets of Cape Town accusing the Governor, Lord Charles Somerset, of “buggering Doctor Barry”. No copy survives. Various accounts of its wording exist. There were even doubts expressed as to whether it had ever really existed, for only one person admitted to having seen it before it disappeared.

William Edwards was the chief suspect, but nothing was ever proved against him. The incident has sparked intensive curiosity amongst popular historians, particularly those writing about Barry, whose sex remains a subject of debate. Serious scholars, however, have shied away from the incident – unable to find an analytical purpose for it, even though it took place in the midst of an intensively studied period of Cape history.

What should spark our curiosity about the placard affair – what questions should we be asking about it as historians? ‘Narrative greed’ leads us to two obvious ones – were Somerset and Barry engaged in sexual relations? And, who put up the placard? The answer to the first question has eluded countless biographers of both Barry and Somerset. For what it is worth, a recent book on Barry has uncovered some persuasive evidence that the doctor was born female though that leaves us no further ahead on the question of relations with Somerset. And with regard to the second question – \who put up the placard – the historian has access to only the same evidence, admittedly voluminous, that was collected in the original case. Can she expect to succeed where a determined public prosecutor under intense political pressure failed some 200 years earlier?

I didn’t consciously think of Ann Stoler’s comment while I wrestled with how to write about the placard scandal in a useful way. Nevertheless, her response to that paper on the Wyldes some 20 years ago doubtless had a role in helping me to work out how I approached this problem. For my purposes, the scandal’s utility lies precisely in recognising its tenuous hold on reality – using that as the object of my analysis rather than an obstacle to my analysis – and in tracing the tactics of ideological warfare that broke out in its aftermath.

As a way of understanding the processes of imperial reform debates, my interest was more in the political management of the scandal than in the alleged sexual improprieties of Lord Charles Somerset and Dr James Barry or the identity of the persons who claimed to have brought them to light. If we look carefully at the sources we can see what was very clear to contemporaries but what historians have missed. What was most significant about the incident was not the contents of the placard itself but the “political ends” – in the words of contemporaries – to which its existence could be put. Despite the dangerous accusations allegedly made in the text (remember our evidence that the placard even existed is tenuous) sex drops out of the public discussion remarkably quickly. What ensues is effectively a public relations struggle between Somerset and his political opponents in both Britain and the Cape, a debate that revolved not around his sexual misconduct but around his tactics of information gathering and the use of spies. Historians can and often should use scandals to ask and answer different questions from the ones that preoccupied those living through them. Because after all, what we are most curious about is working out methods to understand the past as best we can.

Alumni Survey

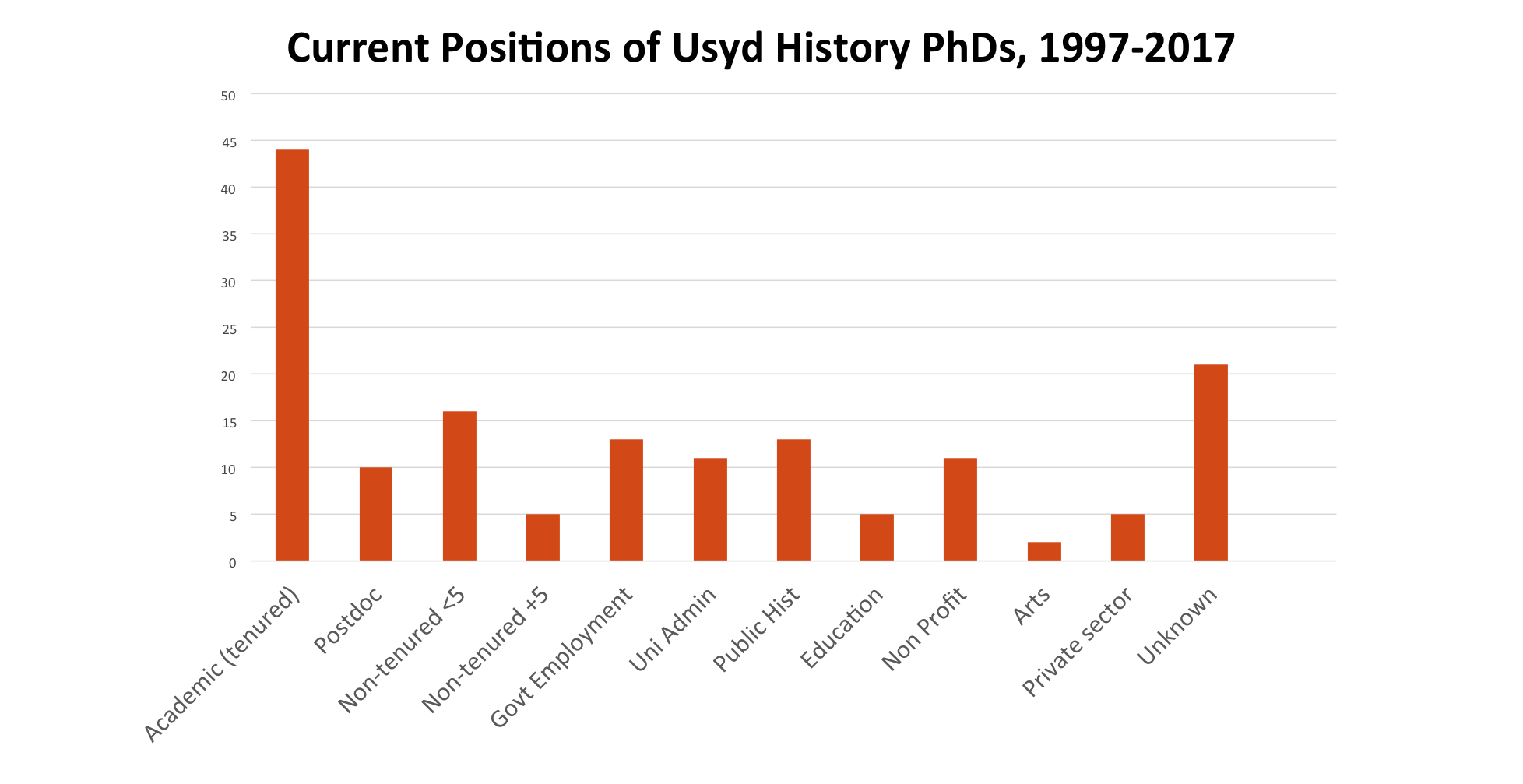

In this blog entry, postgraduate coordinator Dr Frances Clarke reports on the results of a survey she initiated of our PhD recipients over the last twenty years. You can download the results and a presentation she made on “Planning a Future in the Midst of Insecure Job Prospects” for the November 2017 History Postgrad Conference here: Download file

Over the past 20 years, 169 graduates have received doctorates. Subtracting those who have retired, died, or completed in the past five years (most of whom are still looking for full-time work), 139 graduates remain. Of this number:

31.6% have a tenured academic job

11.5% work in public history (as curators, archivists, policy officer, grants coordinators, consultants, city historians, tourism industry employees)

7.9% are in university admin (as research coordinators, faculty research managers, senior strategy and projects officers, senior advisers and governance specialists, research fellows, etc.)

7.1% have a postdoc

7.1% are in government employment (as policy officers, researchers, analysts, etc.)

7.1% work in the non-profit sector or are self-employed (as freelance writers, editors, indexers, research affiliates, or activists)

3.5% are still looking for an academic job after 5 years

3.5% are in teaching (as high school teachers, curriculum developers, textbook designers, etc.)

1.4% are employed in arts-related fields (as journalists, documentary film makers, screen writers).

3.5% are employed in the private sector (as lawyers, consultants, small business owners).

15.1% Could not be located (most likely because they have retired, moved overseas, or left the paid workforce).

The number of individuals in each category:

44 Academic (tenured)

16 Public Hist / Researcher / Editor

11 Univ Admin

10 Postdoc

10 Govt Emp

10 Nonprofit Emp / Self Emp

5 Casual 5+yrs

5 Teaching

2 Arts (journalism/doc film maker/theatre)

5 Private sector (business/law/consultancy)

21 unknown / not currently looking for work / retraining

16 Casual or contract <5 yrs 14 Retired / deceased == 169

Many Paths Beyond the PhD

In this blog entry, postgraduate coordinator Dr Frances Clarke reports on a new initiative, and a recent workshop, for our postgraduate community.

23 November 2017

During the six years that it took to finish my PhD I spent a good deal of my time in a state of mild panic over the idea that I was in my mid 30s and yet had no savings, no superannuation, a massive student loan debt, and not much hope of ever getting a tenured job. Believing—mistakenly, as it turned out—that academic employment was a pipe dream, I spent the six months after my dissertation defense reading a lot of self-help books about graduates who had retrained after the PhD or branched out into diverse fields.

It occurred to me in doing this reading that there was a world of choices I’d never considered—careers just as interesting and politically-fulfilling but potentially less competitive and stressful than a lectureship. Reading this work made me realize that my professors emphasized academic careers not because they were our only possible choices, but because these were the only jobs that most academics knew about. After all, most of us have gone straight from study to teaching without experiencing any other kind of workplace. We have no real idea what it would be like to work as a policy officer for the government, the curator of a museum, an archivist, or a documentary film maker.

But our former PhD students do have this knowledge, since they’ve gone on to all kinds of interesting careers. I discovered this fact while putting together some research on where our history graduates end up for our website. The results of this survey can be found here.

It turns out that our History PhD recipients are everywhere. They are the literary Director of the Melbourne Theatre Company; the Head of the Documentary Division at the Australian Film, TV, and Radio School in Canberra; the Executive Officer at the Historical Publications and Information Section at the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade; the Director of the National Museum in Canberra and the City Historian of Sydney. They teach high school students, run archives and museums, administer universities, create policy, produce journalism, and manage small businesses.

Seeing the diverse ways our graduates put their training to use, it was apparent that one of the things we could do for our students is to introduce them to a range of careers, and do this while they were still completing their training, so that they could have these prospects in mind and hopefully even plan for them. It stood to reason that the best way to do this was to introduce them to former grad students who had once been in their shoes and gone into the workforce.

For our inaugural “Many Paths Beyond the PhD” day, we invited four USyd history alumni to campus to talk about their jobs:

• Dave Trudinger, Director of Energy and Climate Change, Resources & Land Use Branch in the NSW Government’s Department of Premier and Cabinet.

• Emma Dortins, Cultural Heritage Researcher at the Office of Environment & Heritage, NSW

• Richard Lehane, Archivist at State Records Office, NSW.

• Nerida Campbell, Curator, Police and Justice Museum, NSW.

I asked our speakers to describe their career trajectory and talk about how their background in history informed their current role, as well as to give advice to students who might want to consider a job in their areas.

None of the jobs sounded at all how I’d pictured them. Dave, for instance, talked about his work for the NSW government as primarily involving “packaging and presenting information” – sourcing data quickly and efficiently on a whole range of topics for use in a wide variety of ways. Nimbleness and flexibility were clearly essential in his role—and, indeed, in all of the jobs that the four speakers described, since the one thing they had in common was the necessity of dealing with a rapidly changing environment, a diversity of opinions, and a plethora of different tasks.

Emma described her work in managing the state heritage register as encompassing not just questions of what sites to preserve but also dealing with all the intersecting interests that went into such decisions as well as managing a team of staff. In contrast, Richard, working at the State Archives, described spending most of his days deciding what to destroy rather than what to keep, while also noting that archival staff were engaged in activities ranging from the conservation and digitization to curating displays and assessing collections.

For most of us, Nerida’s job was perhaps the easiest to visualize initially, since her role involves telling stories and extracting meaning from objects in ways that are common to all historical work and recognizable to anyone who has ever visited a museum. Yet she explained that even this seemingly straightforward objective requires considerable flexibility since her main dilemma is in finding ways to bring history to life that can appeal simultaneously to a ten-year-old and a retiree and to people from every conceivable walk of life.

One of the most powerful things to come out of the session was simply a sense of expanded possibility. Within the university sector there is constant crisis talk: declining budgets, rampant managerialism, expanding academic workloads, a contracting ‘job market’ for postgraduates. But here were four people with jobs that were interesting and challenging, all using history in various ways.

It reminded me of a piece that I’d read in American Historical Association’s newsletter Perspectives a few years back, which argued that academics’ discussions of a ‘job market crisis’ were overly parochial. Employment in history-related fields has actually been expanding in recent times as local, state, and federal governments pour funding into various history-related activities. It is only our narrow fixation on academic jobs that has prevented us from seeing this trend. In passing on this anxious vision to our students, we leave them with the message that we value only the narrowest range of possibilities for using history, which is simply not the case.

Interestingly, all of our four speakers had been involved in recruiting or hiring, so they had a range of useful advice about ways candidates could prepare for jobs in their fields, or prepare for job interviews.

One of the speakers suggested that all history-related employment required “core competencies.” They suggested that students look at job listings and see what competencies were requested, and then think about ways they could demonstrate proficiency in such areas. Jobs in public history, for instance, typically require the ability to talk to diverse audiences. Anyone wanting to move into this area might thus want to think about publishing in different kinds of venues or giving talks to different kinds of audiences in order to demonstrate such expansiveness.

Similarly, they might think about how to make use of the fact that they are at a large, well-funded research institution, willing to provide them with additional training. Pondering the kinds of training that might prove useful to employers (in statistical analysis, spreadsheets, data management, or digital technology, for instance), they might seek out such training, or ask for it to be provided.

Offering proof of competencies or abilities was another important point that came up. As one of the speakers noted, it’s insufficient for a job candidate to simply refer to their acquisition of particular skills; the candidate has to prove their claim. Stating that one can communicate to broad audiences, for instance, becomes much more credible if accompanied by a statement along the lines of: “I wrote for such and such a website/blog/etc. which is read by such and such an audience, measured in such and such ways.”

And in terms of applying for jobs, everyone emphasized the importance of background research. Nerida said that applicants should call the contact person on a job advertisement and ask about all the different elements of a role. They should make sure that they have questions to ask at the end of the interview. And they should understand something about the institution or culture into which you’re applying to work. Dave advised, for instance, that if the job is with a government department, the applicant should find out what the relevant minister has recently been saying.

Likewise, Nerida noted that anyone looking for a job in a particular museum should go there and see the space – not least because it’s become common to ask applicants for such jobs to come up with a creative proposal for a particular object, with the aim of seeing how well the candidate can think about diverse audiences and communicate ideas. A smart candidate would think not just about the space and the audience, but also try to link their plan to the institution’s own mission (strategic plans and mission statements are especially useful reading when you’re looking for a job).

How to find a job or get some experience in different fields understandably came up numerous times. One of the speakers suggested that postgrads might consider giving their CVs to an executive recruiter such as Charter House or Chandler McCloud. These agencies can sometimes find you casual or fixed-term work in particular areas so that you can get a taste for different kinds of employment.

Richard stressed that there may well be additional training that’s required after the PhD for certain jobs, such as in his field of archival management. For anyone interested in this area, there are online degrees in archival management and graduate programs through the National Library.

But the best way to know if an archive might be your ideal working environment is to go to the regular branch meetings of the Australian Society of Archivists

In a similar way, Nerida said that anyone interested in jobs in museums or public history would do well to go to conferences and meetings of Museums Australia, the main national association for the museums and galleries sector, or simply to attend talks at the State Library, particularly when given by archivists or curators, and make connections with people.

Finally, a couple of more concrete issues came out of the day. Richard promised to take us on a tour the stacks at the NSW archive while giving us an insiders’ view of archival management (excursion!) And several speakers noted the importance of linking one’s topic to broader themes, questions, or fields as well as thinking about the production of a thesis in terms of “project management.”

Both of these ideas, and several of the ones above, will become useful in the professionalisation seminar that the department will run next semester (and hopefully from then on). We’re intending this seminar as a way to help postgraduate students conceptualise their training, break down the discrete parts of what they do, and be able to talk about these to non-academic audiences, and generally claim the expertise and authority that comes from the completion of a history doctorate.

Police and Justice Museum, Sydney, NSW

Postgraduate Conference – The Past and the Curious

Postgraduates of the Department of History at the University of Sydney invite you to attend a two-day interdisciplinary conference held Nov. 30-Dec. 1, 2017.

Some people call historians the detectives of the past. At the University of Sydney’s 2017 postgraduate history conference, we want to know: what are the mysteries you’re uncovering? What are you curiously (and furiously) researching? How are you re-framing our understanding of the established, and seemingly ordinary, past? This two-day conference will allow postgraduate historians from across Australia, and beyond, to share their investigations of the past — and to share in the spirit of historical curiosity.

Themes, covering the ancient to the twenty-first century, include (but are not limited to):

(Re)viewing history through a transnational lens;

Investigations through Oral History;

(Re)viewing Race

Delving into Digital Histories

(Re)viewing Histories of Sexuality

(Re)viewing Gender

(Re)viewing Indigenous Histories

Public Histories

Histories of Emotion

History and (Auto)Biography

(Re)viewing Labor Histories

Click here to explore the Conference website and to view a full conference programme,

Conference: Sovereignty, Economy and the Global Histories of Natural Resources

An International Symposium sponsored by the International Research Award in Global History,

Universities of Sydney, Basel, and Heidelberg

18-19 December 2017

Hosted by the Centre for History and Economics, University of Cambridge

Over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth century natural resources have given shape to the history of sovereignty, law, and commerce across the globe. The struggle to protect, own and extract natural resources has mobilized local authorities, national agencies and international bodies. The Standing Rock water protectors are perhaps most well-known recent example of such histories, but is certainly not the only one. From disputes over social and economic rights to dueling religious and economic understandings of resources and their value, things like carbon, gold and water have determined the lives of national and local communities.

This international symposium invites scholars to examine the history and political ecology of various natural resources – animal, vegetable, or mineral —in the modern era. It asks how natural resources such as carbon, air, and water became the subject of legal, environmental, and economic forces over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth century and how, in turn, these resources have themselves came to shape national and international histories? Papers that focus on the role of local actors, rather than solely international elites, that examine contested spaces and resources beyond the Western Hemisphere, and take an interdisciplinary approach to this global history of natural resources will feature. Papers will address (but are not limited to) the ways in which the political ecology of various natural resources has come to shape:

Border disputes, international territories and national sovereignty

Minority and religious rights

Movement and mobility of people, animals and microbes

Social and economic geographies and spaces

Cultural practices and institutions

Technical expertise and knowledge

The role of nongovernmental and economic agents in local and national contexts

We are pleased to note that Professor Glenda Sluga is co-sponsor of this conference, which was the winning concept in an international competition. A copy of the poster is available here, and you can download the final program here.

Thinkers Guide to the 21st Century

History department staff are regulars in the ‘Thinkers Guide to the 21st Century’ talk series brought to you by the Sydney Ideas/Laureate Research Program in International History.

You can listen to the podcasts on previous topics such as The New International Order (Glenda Sluga), Authoritarianism (Dirk Moses), Feminism in the Age of Populism, and Globalisation (Glenda Sluga and Thomas Adams).

If you missed out on this series, the Laureate Research Program in International History is bringing it back with Sydney Ideas in Semester 2, 2018. The series averaged 300 subscriptions for each event; we hope to keep up the momentum and are holding a competition for next year’s topics. More information from Sydney Ideas soon.

Conference: Monarchies, Decolonisation and Royal Legacies in the Asia-Pacific

Department of History, The University of Sydney,

6-7 December 2017

Organised by Robert Aldrich and Cindy McCreery

Wednesday, 6 December 2017

9.30-10.00 Welcome and Introduction

10.00-11.30 Keynote address

Harshan Kumarasingham (University of Edinburgh), ‘Monsoon Monarchy: The Mercurial Fortunes of the Crown in South Asia since 1947’

11.30-12.00 Morning coffee

12.00-1.00 India and Japan

Jim Masselos (University of Sydney), ‘Decolonised Rulers: Rajas, Maharajas and Others in Postcolonial Times’

Elise Tipton (University of Sydney), ‘From Absolute Monarchy to “Symbol Emperor”: The Transformation of the Japanese Imperial Institution after 1945’

1.00-2.00 Lunch

2.00-3.30 The Dutch East Indies / Indonesia I

Adrian Vickers (University of Sydney), ‘Royal and Other Portraits of Nineteenth-Century Indonesian Rulers in Transition’

Robert Cribb (Australian National University), ‘Faltering Decolonisation: The 1929 Ontvoogding (Detutelisation) of the Aristocracies in the Netherlands Indies’

Jean Gelman Taylor (University of New South Wales), ‘Sultans and the State: Power and Pretence in the Dutch Colony and the Republic of Indonesia’

3.30-4.00 Afternoon tea

4.00-5.00 The Dutch East Indies / Indonesia II

Bayu Dardias (Gadjah Mada University / Australian National University), ‘Surviving Monarchy in Indonesia through the Formation of a Special Region: Yogyakarta, 1940-1950’

Susie Protschky (Monash University), ‘In Disputed Territory: The Dutch Monarchy during the Indonesian National Revolution and in Dutch New Guinea (1945–62)’

5.15 Reception hosted by the Department of History

Day 2, Thursday, 7 December 2107

10.00-11.30 Special Guest Presentation

Milton Osborne (Sydney), ‘The Paradox of Cambodian Royalty, from Norodom (1836-1904) to Sihanouk (1922-2012)’

11.30-12.00 Morning coffee

12.00-1.00 South Pacific Monarchies

Matt Fitzpatrick (Flinders University), ‘The Samoan Monarchy and the Last Years of the German Pacific’

Robert Aldrich and Cindy McCreery (University of Sydney), ‘Colonialism and Monarchy in Oceania’

1.00-2.00 Lunch

2.00-3.00 Australia

Bruce Baskerville (University of Sydney), ‘New South Wales’ Vice-Royal Landscapes: Legacies Hidden in Plain Sight’

Mark McKenna (University of Sydney), ‘Indigenous Australians and the British Crown, 1954-2017’

3.00-3.30 Afternoon Tea

3.30-5.00 Roundtable Discussion

With participation by paper-givers and Miranda Johnson, Sophie Loy-Wilson, Lily Rahim and Andrés Rodriguez (University of Sydney), and Maria Nugent (Australian National University).

7.00 Conference Dinner

*

This is the third in a series of conferences on the history of colonialism and modern monarchies sponsored by the Department of History.

The organisers would like to thank Prof. Chris Hilliard, Chair, Department of History and Dr Miranda Johnson and the Pacific Studies Network for their kind support.

For further information, please contact [email protected] or [email protected]

Postgraduate Scholarship Success

Dear Colleagues,

In what I believe is a department first, two of our postgraduate students, Hollie Pich and Marama Whyte, have simultaneously won Endeavour Awards to undertake research in the U.S. in 2018. These highly-competitive awards are provided by the Australian government to scholars engaging in study, research, or professional development overseas.

Marama has been granted the Endeavour Postgraduate Scholarship to conduct 6-12 months of research at New York University, sponsored by Professor Thomas Sugrue, while Hollie has won an Endeavour Research Fellowship to conduct 4-6 months at Duke University, sponsored by Professor William Chafe.

It what is surely another department record, Marama has also won the Tempe Mann Travelling Scholarship for 2018, which is awarded by the Australian Federation of Graduate Women-New South Wales, taking up an honour that Hollie held the year before.

Warmest congratulations to them both.

—

Dr. Frances M. Clarke

Senior Lecturer &

Postgraduate Coordinator

Department of History

Faculty Teaching Excellence Awards

Many congratulations to our most recent recipients of Faculty Teaching Excellence Awards – Miranda Johnson and Hollie Pich

Dr. Miranda Johnson received a Teaching Excellence Award primarily for her outstanding work in designing and delivering a truly innovative MA unit in Museum and Heritage Studies, HSTY 6987: Presenting the Past, and the resulting public history project called “The Pitcairn Project.”

One of her nominees wrote: “Dr. Johnson has worked assiduously in creating an innovative and intellectually rigorous learning environment for students that has developed and enriched skills in historical investigation, heritage preservation, IT, collaboration, public history, and cultural competency. Students have learned to negotiate with each other, and negotiate many and often difficult ethical hurdles involved with heritage preservation and the public presentation of history. Along the way, students have posted thoughtful public blogposts about their findings, created helpful marking criteria for their own work, and written reflections about their learning experiences in the unit. They have also met experts in heritage preservation, IT development, and some of the artists and historians involved in Tapa making and its history. Having read the blogposts and sat in on some of the workshops as a curious observer, I’ve been impressed with just how engaged and enthusiastic students were. From my own personal experience of co-teaching with Dr. Johnson, I know her to be a creative, caring, and engaged teacher who works tirelessly to create exceptional learning environments. She is a brilliant teacher who is not only committed to research-led teaching, but also to an engaged and inclusive pedagogy that brings out the absolute best in students from a range of backgrounds and abilities. Her work in this particular unit will serve as an exemplary model of project-based learning for the Department and the Faculty as we move to transform the undergraduate curriculum. This is all down to Dr. Johnson’s careful planning, her deep immersion in the literature of a wide array of fields necessary to pull this off, her collaborative mindset, and her critical commitment to producing intellectually rigorous yet accessible public history. Dr. Johnson is simply an exceptional teacher and deserves to be recognized for her extraordinary efforts.”

You can read about some of the work Miranda did last semester with her class on the Pitcairn Project here.

And some of her student blogposts can be found here.

Many congratulations as well to Hollie Pich for receiving a prestigious Dean’s Citation for Excellence in Tutorials with Distinction for her work in HSTY 2671: Law and Order in America and also HSTY 2609: African American History and Culture.

One of Hollie’s support letters noted that “Hollie is the most conscientious tutor with whom I have worked in the six semesters I have taught at the University of Sydney. What struck me most about Hollie was her interest in pedagogy and her endeavours to become the most effective teacher she could be. She solicited feedback from the students in her tutorials and from me during the semester. She also asked me to observe one of her tutorials, and she in turn observed one of my tutorials, after which we met to discuss our respective observations and teaching aims. In observing Hollie’s tutorial and in my interactions with her throughout Semester 1 of 2017, I got a sense of her extraordinary dedication to students. She had a pleasant rapport with her students, facilitated a substantive and invigorating discussion of tutorial readings, achieved wide participation, and orchestrated a well-planned tutorial featuring a combination of group work and tutorial-wide discussion. It was clear that Hollie earnestly cared about her students, treated them with respect, and was approachable while maintaining her professional authority. As one student wrote in the USS survey of HSTY2609, “Hollie’s a great tutor. It’s a pleasure to go to [her class] every week.”

The Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Teaching Excellence Awards program is designed to recognize and reward the teaching excellence of staff at all career levels, to encourage teachers to engage in reflective teaching practices, and to promote and support the development of high quality and innovative teaching.

Recipients have demonstrated an evidence informed approach to critical reflection on teaching and learning, evaluation of their teaching practice, engagement with higher educational research, and a focus on improving student learning.

Awards were presented by Professor Annamarie Jagose on Monday, 6 November 2016 at MacLaurin Hall. Unfortunately, Hollie Pich was in the US on a research trip and unable to pick up her award in person.

A few of the award recipients, including Miranda, were invited to give a brief presentation on how they were able to engage with and respond to evidence of effective student learning to successfully achieve excellence in teaching.

Please join us in congratulating Miranda and Hollie and the other recipients on their Teaching Excellence Awards, in the company of their family and friends.

The 2017 Teaching Awards recipient are:

Teaching Excellence Award

Dr Gareth Bryant (SSPS)

A/Professor Damien Cahill (SSPS)

Dr Mark de Vitis (SLAM)

Dr Amanda Elliot (SSPS)

Dr Marianne Fenech (SSESW)

Dr Huw Griffiths (SLAM)

A/Professor Pablo Guillen (Economics)

Dr Miranda Johnson (SOPHI)

A/Professor David Kim (Economics)

Dr Guy Redden (SOPHI)

Dr Brigid Rooney (SLAM)

Dr Jen Scott Curwood (SSESW)

Dr Aim Sinpeng (SSPS)

Professor Rodney Smith (SSPS)

Dr Louise Sutherland (SSESW)

Dr David Ubilava (Economics)

Dean’s Citation for Excellence in Tutorials with Distinction

Georgia Carr (SLAM)

James Goulding (SSESW)

Hollie Pich (SOPHI)

Tim Smartt (SOPHI)

Alix Thoeming (SOPHI)

Dean’s Citation for Excellence in Tutorials

Ella Collins-White (SLAM)

Alex Cubis (SLAM)

Karla Elias (SLAM)

Danica Jenkins (SLC)

Michael Leadbetter (SLC)

James Monaghan (SOPHI)

Wyatt Moss-Wellington (SLAM)

Cressida Rigney (SLAM)

Angela Rose (SSESW)

Margaret Van Heekeren (SLAM)

Peter Wasson (SSESW)