History department staff are regulars in the ‘Thinkers Guide to the 21st Century’ talk series brought to you by the Sydney Ideas/Laureate Research Program in International History.

You can listen to the podcasts on previous topics such as The New International Order (Glenda Sluga), Authoritarianism (Dirk Moses), Feminism in the Age of Populism, and Globalisation (Glenda Sluga and Thomas Adams).

If you missed out on this series, the Laureate Research Program in International History is bringing it back with Sydney Ideas in Semester 2, 2018. The series averaged 300 subscriptions for each event; we hope to keep up the momentum and are holding a competition for next year’s topics. More information from Sydney Ideas soon.

Conference: Monarchies, Decolonisation and Royal Legacies in the Asia-Pacific

Department of History, The University of Sydney,

6-7 December 2017

Organised by Robert Aldrich and Cindy McCreery

Wednesday, 6 December 2017

9.30-10.00 Welcome and Introduction

10.00-11.30 Keynote address

Harshan Kumarasingham (University of Edinburgh), ‘Monsoon Monarchy: The Mercurial Fortunes of the Crown in South Asia since 1947’

11.30-12.00 Morning coffee

12.00-1.00 India and Japan

Jim Masselos (University of Sydney), ‘Decolonised Rulers: Rajas, Maharajas and Others in Postcolonial Times’

Elise Tipton (University of Sydney), ‘From Absolute Monarchy to “Symbol Emperor”: The Transformation of the Japanese Imperial Institution after 1945’

1.00-2.00 Lunch

2.00-3.30 The Dutch East Indies / Indonesia I

Adrian Vickers (University of Sydney), ‘Royal and Other Portraits of Nineteenth-Century Indonesian Rulers in Transition’

Robert Cribb (Australian National University), ‘Faltering Decolonisation: The 1929 Ontvoogding (Detutelisation) of the Aristocracies in the Netherlands Indies’

Jean Gelman Taylor (University of New South Wales), ‘Sultans and the State: Power and Pretence in the Dutch Colony and the Republic of Indonesia’

3.30-4.00 Afternoon tea

4.00-5.00 The Dutch East Indies / Indonesia II

Bayu Dardias (Gadjah Mada University / Australian National University), ‘Surviving Monarchy in Indonesia through the Formation of a Special Region: Yogyakarta, 1940-1950’

Susie Protschky (Monash University), ‘In Disputed Territory: The Dutch Monarchy during the Indonesian National Revolution and in Dutch New Guinea (1945–62)’

5.15 Reception hosted by the Department of History

Day 2, Thursday, 7 December 2107

10.00-11.30 Special Guest Presentation

Milton Osborne (Sydney), ‘The Paradox of Cambodian Royalty, from Norodom (1836-1904) to Sihanouk (1922-2012)’

11.30-12.00 Morning coffee

12.00-1.00 South Pacific Monarchies

Matt Fitzpatrick (Flinders University), ‘The Samoan Monarchy and the Last Years of the German Pacific’

Robert Aldrich and Cindy McCreery (University of Sydney), ‘Colonialism and Monarchy in Oceania’

1.00-2.00 Lunch

2.00-3.00 Australia

Bruce Baskerville (University of Sydney), ‘New South Wales’ Vice-Royal Landscapes: Legacies Hidden in Plain Sight’

Mark McKenna (University of Sydney), ‘Indigenous Australians and the British Crown, 1954-2017’

3.00-3.30 Afternoon Tea

3.30-5.00 Roundtable Discussion

With participation by paper-givers and Miranda Johnson, Sophie Loy-Wilson, Lily Rahim and Andrés Rodriguez (University of Sydney), and Maria Nugent (Australian National University).

7.00 Conference Dinner

*

This is the third in a series of conferences on the history of colonialism and modern monarchies sponsored by the Department of History.

The organisers would like to thank Prof. Chris Hilliard, Chair, Department of History and Dr Miranda Johnson and the Pacific Studies Network for their kind support.

For further information, please contact [email protected] or [email protected]

Postgraduate Scholarship Success

Dear Colleagues,

In what I believe is a department first, two of our postgraduate students, Hollie Pich and Marama Whyte, have simultaneously won Endeavour Awards to undertake research in the U.S. in 2018. These highly-competitive awards are provided by the Australian government to scholars engaging in study, research, or professional development overseas.

Marama has been granted the Endeavour Postgraduate Scholarship to conduct 6-12 months of research at New York University, sponsored by Professor Thomas Sugrue, while Hollie has won an Endeavour Research Fellowship to conduct 4-6 months at Duke University, sponsored by Professor William Chafe.

It what is surely another department record, Marama has also won the Tempe Mann Travelling Scholarship for 2018, which is awarded by the Australian Federation of Graduate Women-New South Wales, taking up an honour that Hollie held the year before.

Warmest congratulations to them both.

—

Dr. Frances M. Clarke

Senior Lecturer &

Postgraduate Coordinator

Department of History

Chifley College Prize Ceremony

NB: This blog entry comes courtesy of the students and staff at Chifley College Senior Campus, Mount Druitt. Many thanks especially to Dianne Harper.

Prize-winners Laura Sole, Rowzen Caro, and Micaila Bellanto

The development of cults in Roman Egypt was influenced by both Egyptian and Greek traditions, and the abolition of the slave trade played out very differently in England and America. Participants in the Cult of Isis were promised the secrets of life and death and the transatlantic slave trade had both long term economic and social effects.

These are some of the interesting facts that Chifley College Senior Campus students explored while researching their Ancient and Modern History Historical Investigations.

Rowzen Caro and Micaila Bellanto were named the joint winners of the 2017 Sydney University Modern History Essay Competition, one of the school’s top prizes for Year Eleven History Students.

Micaila, a prolific reader and writer about Modern History issues was praised for writing an essay on the transatlantic slave trade that “was well-written and well-presented, and demonstrates both sound knowledge of the content, and a sophisticated University-level approach to the topic. Micaila’s explanation of the shift in the status of Africans in colonial America due to changing demands for labour demonstrated a sophisticated historical analysis.”

Laura Sole, the winner of the 2017 Sydney University Ancient History Essay Competition, explored the variety of religious practices in 4th century Egypt. The judges thought the examples chosen to do this showed Laura was “thinking like an historian” and was “well-researched and argued, the essay showed good attention to the historiographical debate and had a really strong conclusion.“

The essay competition is held in conjunction with the Department of History at Sydney University, and judged by academics from both the modern and ancient disciplines. Sydney University and Chifley College Senior Campus have been working together since 2014 as part of an equity program in order to encourage students to achieve academic excellence and to consider University as an option.

In 2017, six students have been awarded conditional scholarships under the Sydney University E12 program. As well as the essay competition, the partnership includes a mentoring program with History Extension students as well as regular visits of senior students to the university campus.

Rowzen, who placed first in the competition, spent some time talking to current students at Sydney University, chatting about school and university life. She believes that the chance to work alongside university students, and have them support her in her studies, provides an opportunity “to get a feel for what University will be like. It’s really useful, it makes me think about what I will do after my HSC, and helpful in setting goals for academic success.” The judges said that her essay was “written with flair, with a good critical evaluation of a range of sources, and makes a convincing argument.”

Micaila, Laura and Rowzen were presented with their awards on November 10th, by Dr Frances Clarke and Associate Professor Michael McDonnell from Sydney University, in front of many proud parents, carers, teachers, and fellow students. The awards are presented to those students who have explored an area of history to a high academic standard, using sources, exploring historiographical issues and drawing sophisticated conclusions.

Click here for more information about the Department of History’s outreach and social inclusion program

Prize-winner Micaila Bellanto with her mum, Jodie Bellanto

Faculty Teaching Excellence Awards

Many congratulations to our most recent recipients of Faculty Teaching Excellence Awards – Miranda Johnson and Hollie Pich

Dr. Miranda Johnson received a Teaching Excellence Award primarily for her outstanding work in designing and delivering a truly innovative MA unit in Museum and Heritage Studies, HSTY 6987: Presenting the Past, and the resulting public history project called “The Pitcairn Project.”

One of her nominees wrote: “Dr. Johnson has worked assiduously in creating an innovative and intellectually rigorous learning environment for students that has developed and enriched skills in historical investigation, heritage preservation, IT, collaboration, public history, and cultural competency. Students have learned to negotiate with each other, and negotiate many and often difficult ethical hurdles involved with heritage preservation and the public presentation of history. Along the way, students have posted thoughtful public blogposts about their findings, created helpful marking criteria for their own work, and written reflections about their learning experiences in the unit. They have also met experts in heritage preservation, IT development, and some of the artists and historians involved in Tapa making and its history. Having read the blogposts and sat in on some of the workshops as a curious observer, I’ve been impressed with just how engaged and enthusiastic students were. From my own personal experience of co-teaching with Dr. Johnson, I know her to be a creative, caring, and engaged teacher who works tirelessly to create exceptional learning environments. She is a brilliant teacher who is not only committed to research-led teaching, but also to an engaged and inclusive pedagogy that brings out the absolute best in students from a range of backgrounds and abilities. Her work in this particular unit will serve as an exemplary model of project-based learning for the Department and the Faculty as we move to transform the undergraduate curriculum. This is all down to Dr. Johnson’s careful planning, her deep immersion in the literature of a wide array of fields necessary to pull this off, her collaborative mindset, and her critical commitment to producing intellectually rigorous yet accessible public history. Dr. Johnson is simply an exceptional teacher and deserves to be recognized for her extraordinary efforts.”

You can read about some of the work Miranda did last semester with her class on the Pitcairn Project here.

And some of her student blogposts can be found here.

Many congratulations as well to Hollie Pich for receiving a prestigious Dean’s Citation for Excellence in Tutorials with Distinction for her work in HSTY 2671: Law and Order in America and also HSTY 2609: African American History and Culture.

One of Hollie’s support letters noted that “Hollie is the most conscientious tutor with whom I have worked in the six semesters I have taught at the University of Sydney. What struck me most about Hollie was her interest in pedagogy and her endeavours to become the most effective teacher she could be. She solicited feedback from the students in her tutorials and from me during the semester. She also asked me to observe one of her tutorials, and she in turn observed one of my tutorials, after which we met to discuss our respective observations and teaching aims. In observing Hollie’s tutorial and in my interactions with her throughout Semester 1 of 2017, I got a sense of her extraordinary dedication to students. She had a pleasant rapport with her students, facilitated a substantive and invigorating discussion of tutorial readings, achieved wide participation, and orchestrated a well-planned tutorial featuring a combination of group work and tutorial-wide discussion. It was clear that Hollie earnestly cared about her students, treated them with respect, and was approachable while maintaining her professional authority. As one student wrote in the USS survey of HSTY2609, “Hollie’s a great tutor. It’s a pleasure to go to [her class] every week.”

The Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Teaching Excellence Awards program is designed to recognize and reward the teaching excellence of staff at all career levels, to encourage teachers to engage in reflective teaching practices, and to promote and support the development of high quality and innovative teaching.

Recipients have demonstrated an evidence informed approach to critical reflection on teaching and learning, evaluation of their teaching practice, engagement with higher educational research, and a focus on improving student learning.

Awards were presented by Professor Annamarie Jagose on Monday, 6 November 2016 at MacLaurin Hall. Unfortunately, Hollie Pich was in the US on a research trip and unable to pick up her award in person.

A few of the award recipients, including Miranda, were invited to give a brief presentation on how they were able to engage with and respond to evidence of effective student learning to successfully achieve excellence in teaching.

Please join us in congratulating Miranda and Hollie and the other recipients on their Teaching Excellence Awards, in the company of their family and friends.

The 2017 Teaching Awards recipient are:

Teaching Excellence Award

Dr Gareth Bryant (SSPS)

A/Professor Damien Cahill (SSPS)

Dr Mark de Vitis (SLAM)

Dr Amanda Elliot (SSPS)

Dr Marianne Fenech (SSESW)

Dr Huw Griffiths (SLAM)

A/Professor Pablo Guillen (Economics)

Dr Miranda Johnson (SOPHI)

A/Professor David Kim (Economics)

Dr Guy Redden (SOPHI)

Dr Brigid Rooney (SLAM)

Dr Jen Scott Curwood (SSESW)

Dr Aim Sinpeng (SSPS)

Professor Rodney Smith (SSPS)

Dr Louise Sutherland (SSESW)

Dr David Ubilava (Economics)

Dean’s Citation for Excellence in Tutorials with Distinction

Georgia Carr (SLAM)

James Goulding (SSESW)

Hollie Pich (SOPHI)

Tim Smartt (SOPHI)

Alix Thoeming (SOPHI)

Dean’s Citation for Excellence in Tutorials

Ella Collins-White (SLAM)

Alex Cubis (SLAM)

Karla Elias (SLAM)

Danica Jenkins (SLC)

Michael Leadbetter (SLC)

James Monaghan (SOPHI)

Wyatt Moss-Wellington (SLAM)

Cressida Rigney (SLAM)

Angela Rose (SSESW)

Margaret Van Heekeren (SLAM)

Peter Wasson (SSESW)

History, migration and deradicalisation

In this blogpost, current Honours student, Stephanie Barahona interviews former Honours student MIrela Kadric about history, migration, and deradicalisation.

Note: This article originally appeared in Honi Soit, Semester 2, Week 7, 2017. Many thanks to the editors and to Steph Barahona for their permission to reproduce it here.

It seems like Mirela Kadrić has accomplished so much in such a short time.

At 23, she is an experienced academic writer and researcher, and a revered community leader. She credits much of her success to her Muslim faith, and her twofold passion for history and education. However, it took a lot of self-reflection and courage to come to this point in her life, and there is a lot more she hopes to achieve next.

“I think I’d like to be a positive role model for Muslim women, to show them that you can get to where you want with determination and grasping every opportunity that presents itself to you.”

Born in Bosnia in 1994, Kadrić arrived in Australia as an infant with her mother and father who had sought refuge from the horrors of the Bosnian War. The Srebrenica genocide that Kadrić and her family fled from is regarded by the United Nations as the “worst [conflict] on European soil since the Second World War.” While she has no recollection of the events that unfolded before her arrival in Australia, she explains that studying history has given her a greater appreciation of what her parents went through, as well as a better understanding of her own identity as a Bosnian-Muslim.

“When you’re a little kid you don’t take notice of the struggle. When people ask me [about the war], I say from memory I didn’t live through the struggle, but now that I understand everything, it was hard for my parents,” she reflects. “History has actually defined my outlook on life. If I hadn’t studied history, I don’t think I would have understood the complexity of my own identity.”

In 2016, Kadrić completed her history honours thesis at the University of Sydney. Earning first class honours, her thesis focused on how the Muslim population of Bosnia-Herzegovina developed a distinct Bosniak identity under the leadership of Alija Izetbegovic, from the aftermath of World War Two and the Dayton Peace Accords of 1995. She explains that it was through honours that she was able to develop the research tools necessary to aid her in this journey of self-discovery.

“I started to think critically about myself and the people around me and about the world… and so when I wanted to do honours I started to ask people who were Bosnian, ‘how do you think about yourself?’ … and no one really said they were Bosnian Muslim which was interesting due to this double identity.”

Kadrić attributes this concept of a “double identity” to the categorisations of the Bosnian identity during the latter half of the twentieth century. As she describes it, the idea of being solely Bosnian did not translate in the nationalistic and global sense. For this reason, all Bosnians were often seen as Muslim. Religion could not be separated from one’s national identity, which in turn often contributed to the existing tensions experienced within the region; while outsiders often assumed Bosnian was synonymous with Muslim, some in the region found this affronting.

“Bosnians were defined as Muslims. For example, you go and meet a Bosnian and they’d be called Muslim. But the question for me was like, why can’t we just call them Bosnian and see them as Bosnians since we are from Bosnia — we are not from ‘Muslim land’. So it didn’t add up.”

Discovering this had informed her of her own double identity, and those of many other Muslims in the post-Trump age.

“I started to understand that there was a double identity at play — that I had a double identity being a Bosnian and a Muslim.You can see that today with a lot of Muslims … I feel like more Muslims are turning away from their faith as they don’t want to associate themselves with the notion of ‘extremism.’”

However, she does not point the finger of blame at those who choose to opt out of their faith.

“I don’t blame them… because you get so sick and tired of trying to justify yourself and defend yourself. And no matter what happens in the world, it is the Muslims who have to defend their own actions and faith.”

Kadrić is now studying a Masters of Islamic Studies on a scholarship at Charles Sturt University, through the Islamic Sciences and Research Academy Australia (ISRA). Established in Sydney in 2009, ISRA is the country’s first and only Islamic research-based organisation that is affiliated with a university.

Kadrić reveals that she had planned to take a break from studying this year, but saw this as an opportunity to further explore her faith and give back to her community at the same time. After having published two of her honours seminar papers through the Chicago Journal and ISRA, she was approached by the organisation’s director, Dr. Mehmet Ozalp, to join the team as a research officer. One of the main focuses of her research looks at understanding the perceptions of Muslim identities in Australian society.

“The project that I am doing, it’s being done for Charles Sturt University by the Centre for Islamic Studies and Civilisation (CISC)… The aim is to trace the patterns and factors that led to the transformation in Muslim youth [age 20 to 28] from struggling with their Muslim identity and place in Australian society by being labelled as unpromising youths, to becoming upstanding and contributing citizens engaged in positive action.”

Ultimately, she explains, the centre wishes to explore what is called “Muslim youth positive transformations.” The project aims to seek out ways to depart from the stereotype of Muslim youth being key targets for radicalisation — something that has never been done before.

“Muslim youth positive transformations suggests successful integration, inclusiveness, and commonality with the wider Australian population, and dismisses notions of Muslim youth as an ‘out-group’.”

Asked about how her degree and her experience with the organisation has shaped her faith, she says, “I think the knowledge that I am gaining now is a bit more personal… because we are now learning how to talk about our faith with people of other faiths and how we can talk about it in a way that they understand us… as they say, we are one in the same. We all have our differences, but it is all about trying to find that middle ground.”

Towards the end of our discussion, I ask Mirela about her goals for the future. She talks about her passion for education.

“Education gives you a sense of fulfilment,” she says, “and that is what got me here today.”

Her ultimate goal is to become an academic and teach history at a university level.

“I think tertiary education is the perfect place to inspire a new generation of students, and as interest in the arts is slowly declining, especially with government cuts, I’d like to inspire students to engage with arts and study history. Having the opportunity to study history opened up so many doors that I could never have considered, or imagined could direct me to where I am now — and hopefully, to where I want to be.”

Art: Mirela Kadric; Check out: ‘Art by Lela’ on Facebook

Archival adventures in London

A slightly embarrassing confession: before my supervisor mentioned it, the need to travel overseas to do archival work had barely occurred to me. This might sound quite surprising coming from a PhD student in a history department, but in the historical work I have previously done I’ve used sources accessible online or in widely available books – for example, UK Hansard. My current research has led me to sources that are not available by digital means, and so in September of this year I went to London to visit the National Archives of the UK and the British Library to view them.

This is my first year of postgraduate study and I am working on the intellectual history of free trade and liberalism in Britain in the early-to-mid nineteenth century. I came to this from an undergraduate major in political science, and now working in a history department has been eye-opening for me in many ways. I have been playing catch-up with stacks of classic works of history, learning to ask new questions about my subjects, and thinking carefully about the nature of the work I am doing. Learning about archival research and doing it myself has been one of the most unusual experiences of my study so far.

This was my first research trip and a relatively quick one – I had four weeks to photograph as much as I could to bring back home to study and write about here. I was working mainly in the archive of a UK government body called the Board of Trade, located at the National Archives. I found certain information about the contents of this archive online, such as the names of its different sections and documents that comprise these, but I had no indication as to what it was all going to be like physically. This uncertainty made me very thoughtful about how the materiality of research materials and processes can shape the kind of work I am able to produce. What if the documents I wanted to see were extremely lengthy or difficult to manage? I would need to spend a long time copying each one and this would necessarily limit the amount of material I could collect in the time I had. If the documents were very short and light on details, however, I might need to seriously rethink aspects of my topic and expand or change the range of sources I planned to use.

I was concerned about making sure my time in London was productive and ended up becoming a bit anxious as a result of not having a clear idea of the nature of my archive. To help sort out my concerns I made a plan that would serve in a range of scenarios, setting out a core collection of documents that I especially wanted to see, as well as a larger range of things of interest. I kept firmly in mind that this was my very first research trip and that I needed to find a balance between being ambitious and realistic.

A particular challenge was deciding how I would gather all my research materials and how to store them securely. I knew I would most likely be taking thousands of photographs and wanted to have them organised in a way that would make them easily accessible for ease of use by my future self. I went with the programme Evernote, which can be used across multiple devices and would allow me to organise my photos very neatly. I have found it an extremely useful tool for taking photos and organising materials, but I would have benefitted from some deeper investigation into how it works. My tablet’s internal memory eventually came close to full capacity and I discovered that Evernote would not work if I shifted the application to my external memory card. This seems unusual for a programme that is quite clearly designed to store things – eating up internal memory is a nuisance and something I could only “solve” by resorting to using my phone to take photos for the last few days of my trip. I was also caught out by Evernote’s upload limit, and ended up needing to pay for a premium subscription to expand my upload allowance. Despite these setbacks (extremely stressful at the time!) Evernote worked quite well and, importantly, enabled me to store my photos online as well as in my devices’ memory to greatly reduce the chance of anything being lost permanently.

Difficulties aside, it was very exciting to actually be in London and feel a sense of being in the history I am writing. The archives presented many intriguing and funny moments: unfolding huge ornate petitions from groups of silk makers, holding letters handwritten by such prominent figures as Robert Peel, reading a note from one distinguished politician to another asking to catch up for a gossip session. I enjoyed even such simple things as feeling different kinds of paper and admiring beautiful handwriting. Spending long days on my feet was not always fun, but sheer fascination with everything I looked through made it easy.

I could have visited other archives, including some outside London, on this trip, but decided to stay focused on the Board of Trade as the point of connection between many of the people I am interested in and a curious institution in its own right. After just my first week looking over these materials, I began to see many interesting associations between individuals and details of their roles in or adjacent to the Board, and to free trade debates. I realised that I will gain so much more from visiting other archives on another trip when I have a more generous amount of time to spend and a clearer idea of what precisely I would be looking at. Documents like personal correspondence will be so much more meaningful to me once I have better general knowledge of the webs of connected people and institutions in my period of interest.

This research trip was a steep learning curve for me. I got a lot of “new things” out of the way, and I know that walking into an unfamiliar archive will seem much less daunting now. Figuring out how to manage my sometimes erratic attention span is an ongoing issue, as is management of adequate coffee-and-cake breaks. I am very much looking forward to my next trip, and until then I have thousands of pages of meeting minutes to keep me occupied.

The 2nd Bicentennial Australian History Lecture

50,000 years of Australian History: a plea for interdisciplinarity

Professor Lynette Russell, Monash Indigenous Studies Centre, Monash University

The 2nd Bicentennial Australian History Lecture, hosted by the Department of History, the University of Sydney

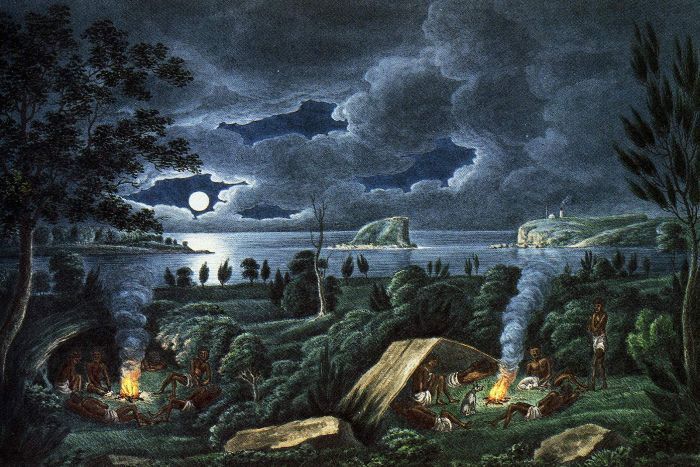

Joseph Lycett – Aborigines Resting by a Camp Fire near the Mouth of the Hunter River, Newcastle, NSW. (National Library of Australia)

How do we understand, imagine, visualise and create narratives for 50,000 years of Australian history?

As commonly presented, Australia’s past seems to consist of 230 years of European colonisation and over 50,000 years of Aboriginal culture, the former the purview of historians and the latter of archaeologists. Yet it presents striking opportunities for a truly integrated and seamless deep continental history, combining disciplines and methodologies.

Such a history would consider the full range of human experience from arrival, through changes in climate, technologies and belief systems to interactions with Maccassan, Portuguese, Dutch, French and finally the British. It would stretch across 2500 unbroken generations of people birthed, nurtured and sustained: people who modified landscapes, hunted, sang songs, practised religion and buried their dead.

This lecture argues for mixing epistemologies to create historical narratives of the deep past that may be taught in schools and universities, presented in museums and popular culture, and proudly shared by all Australians.

ABOUT THE SPEAKER

Professor Lynette Russell is Director of the Monash Indigenous Studies Centre, Monash University, and Node Director of the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence in Australian Biodiverstiy and Heritage. She traces her Aboriginal ancestry via her grandmother from Western Victoria with connections into Tasmania and the Bass Strait islands; on the other side she is descended from transported convicts.

Lynette has a PhD in history from the University of Melbourne and has taught and researched in historical studies for over twenty years. In 2015 she was visiting fellow at All Souls College Oxford. Her monographs include: Hunt them, Hang Them: The Tasmanians in Port Phillip, 1841-1842 (2016); Roving Mariners: Aboriginal Whalers in the Southern Oceans 1790-1870 (2012); Appropriated Pasts: Archaeology and Indigenous People in Settler Colonies, coauthored with Ian McNiven (2005); A Little Bird Told Me (2002); and Savage Imaginings: Historical and Contemporary Representations of Australian Aboriginalities (2001). She is the current President of the Australian Historical Association.

The Bicentennial Australian History Lecture is a biennial public lecture hosted by the Department of History in the School of Philosophical and Historical Inquiry, University of Sydney. Distinguished historians offer engaged and critical perspectives on Australia’s past and the legacies of colonisation.

Date: Thursday 19 October, 2017

Time: 6 – 7.30pm

Please join us before the lecture for a reception in the Nicholson Museum at 5pm.

Venue: General Lecture Theatre, The Quadrangle, The University of Sydney. Venue location

Cost: Free and open to all with online registrations required

Register: here

NSW Premier’s History Prize Finalists and Winners

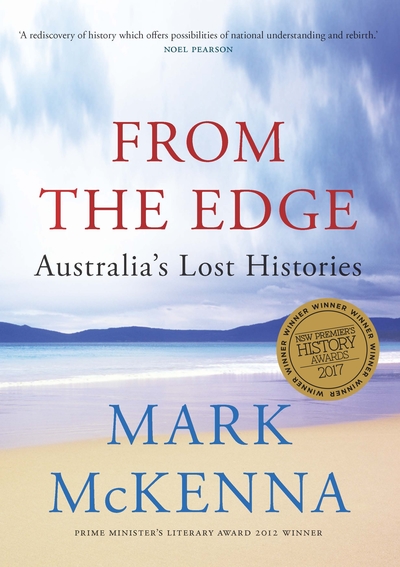

Many congratulations to Mark McKenna for winning the Australian History Prize for his book From the Edge: Australia’s Lost Histories

And to Peter Hobbins for winning with NSW Community and Regional History Prize with Annie Clark and Ursula Frederick for Stories from the Sandstone, the book that grew out of the Quarantine Station project.

The Department also congratulates Miranda Johnson, whose The Land Is Our History was one of the three finalists for the extremely competitive General History Prize.

It’s an honour for the Department to have been so well represented in the Premier’s Awards this year.

Chris Hilliard

Chair, Department of History

Former Student Steph Mawson Wins Prestigious Prizes

Steph Mawson, who did her Honours and MPhil degree with the department (winning numerous prizes, the University Convocation Medal, and co-founding the student journal History in the Making), has continued her award-winning ways with two articles that she wrote up from her MPhil research.

Steph’s article entitled “Convicts or Conquistadores?: Spanish Soldiers in the Seventeenth-Century Pacific,” published in the prestigious journal, Past & Present (232 [2016], pp. 87-125), won the Royal Historical Society’s (RHS) Alexander Prize.

Named for L.C. Alexander, the founding secretary of the RHS who endowed the original award, the Alexander Prize “…is awarded for an essay or article based on original historical research, by a doctoral candidate or those recently awarded their doctorate, published in a journal or an edited collection of essays.” Prize winners receive a silver medal, two hundred and fifty pounds and an invitation to submit a further article for consideration by the editors of the RHS’ in house journal Transactions.

In awarding Stephanie the prize the judges remarked:

“This ambitious and important article examines the ragtag army which colonized the Spanish East Indies during the seventeenth century. Its deep archival research reveals ordinary soldiers to have been quite unlike their stereotypical depiction as conquistadores. They were a motley collection of criminals, vagrants and fugitives, many conscripted and mostly from New Spain, who seldom shared the spoils of conquest with their commanding officers. The author at once restores agency to these historical figures and displays its narrow limits. Mutiny and desertion were among the few pathways open to the conscripted and the mistreated. Such a small, impoverished and volatile force could not be relied upon to achieve Spain’s imperial ambitions, resulting in the recruitment of increasing numbers of indigenous troops. The article offers a compelling portrait of the early modern Philippines. Its intertwining of social and military history makes it distinctive among submissions dominated by intellectual history. Its success in ‘[h]umanising and complicating the face of imperialism’ invites historians of empire to take account of the conflicting interests and motives of the colonisers and their correspondingly diverse relationships to the colonised.”

For further information, see:http://pastandpresent.org.uk/congratulations-stephanie-mawson/

If that wasn’t enough, Steph also won the Dr. Robert F. Heizer Award for 2016 for another article she published in Ethnohistory, entitled “Philippine Indios in the Service of Empire: Indigenous Soldiers and Contingent Loyalty” (Vol. 63, No. 2 [2016], 381-413).

The award is given to the article that the committee believes exemplifies the best in Ethnohistorical research. The committee was impressed with the originality of the research, the strength of analysis, and the importance of its scholarly intervention.

For more on the award, please see: http://ethnohistory.org/index.php/awards-and-prizes/article-award/

Steph is now completing her PhD at Cambridge University.

Many congratulations to Steph!