The ANZAC Nurses of the Coast-Prince Henry

https://sites.google.com/view/anzacnursesprincehenry/home

In his authoritative work Why History Matters, John Tosh observes how communities “are confronted by the paradox of a society which is immersed in the past yet detached from its history.” Tosh’s contention profoundly underscores both the genesis of this project, as well as the fundamental importance of its very purpose.

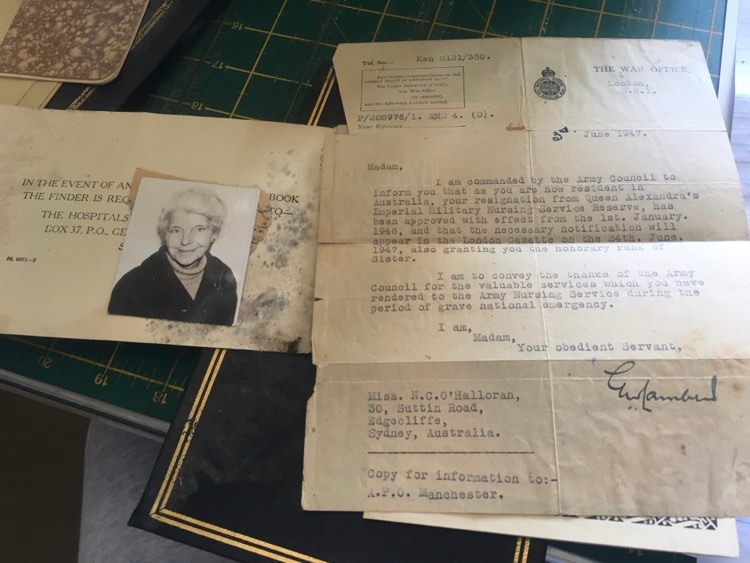

I was fortunate to be accepted by the Prince Henry Hospital Museum based in Little Bay. On my first day as a volunteer, I was tasked to itemise old registration records of nurses from the former hospital when I eventually came across two particular nurse’s records included documents and photographs pertaining to their services during the Second World War. My immediate impression was that this could potentially form an entirely original project by presenting an apparently untold piece of Australian war accounts – from an enlisted nurse’s perspective. This concept was mainly due to an inherent belief that the general consensus of Australian army nursing, particularly during both world wars, at least, was relatively unknown or entirely remote altogether. Moreover, to focus primarily on a specific individual’s history in this regard would also be extremely unlikely as to have any previous form of official historical publication.

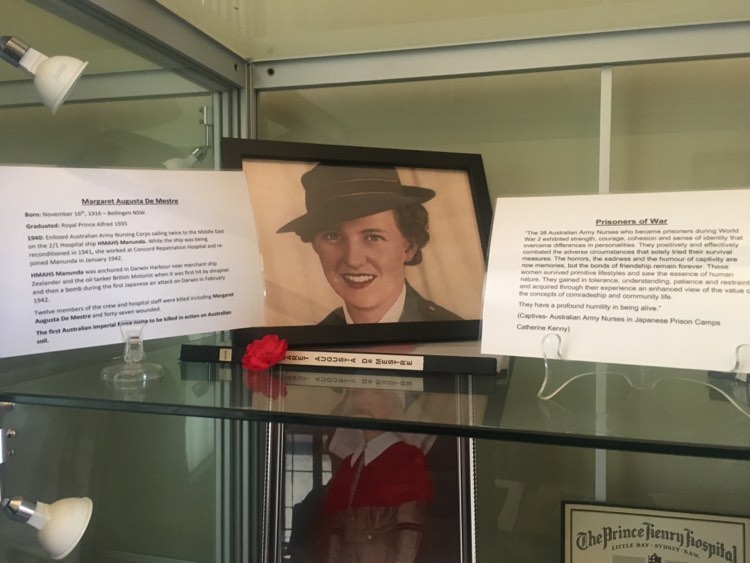

Hence, the implicit argument of Profiles in Valour is how the role played by Australian army nursing in twentieth-century’s cataclysmic events has been highly underplayed or historically unappreciated within this historical discourse. Names such as ‘Bessie’ Pocock, Margaret de Mestre, Vivian Bullwinkle, and Muriel Knox Doherty should be included alongside those annals of the Australian military iconography, next to Gallipoli, John Simpson Kirkpatrick and his donkey, the Rats of Tobruk, and the Kokoda Track. Jan Basset’s exordium in her monograph Guns and Brooches somewhat confirmed this suspicion accentuating how the historiography of Australian army nursing has been unilaterally neglected by most historians until the 1980s. Fortunately, her work, along with notable other studies by Catherine Kenny, Peter Rees, and Rupert Goodman have crucially filled gaps within its historiography which otherwise may have been lost forever. Therefore, this project relies exclusively on such secondary materials in order to create, as per Bassett’s dictum, an ‘impressionistic’ historically profile of an individual ANZAC nurse to arguably illustrate their own wartime experiences.

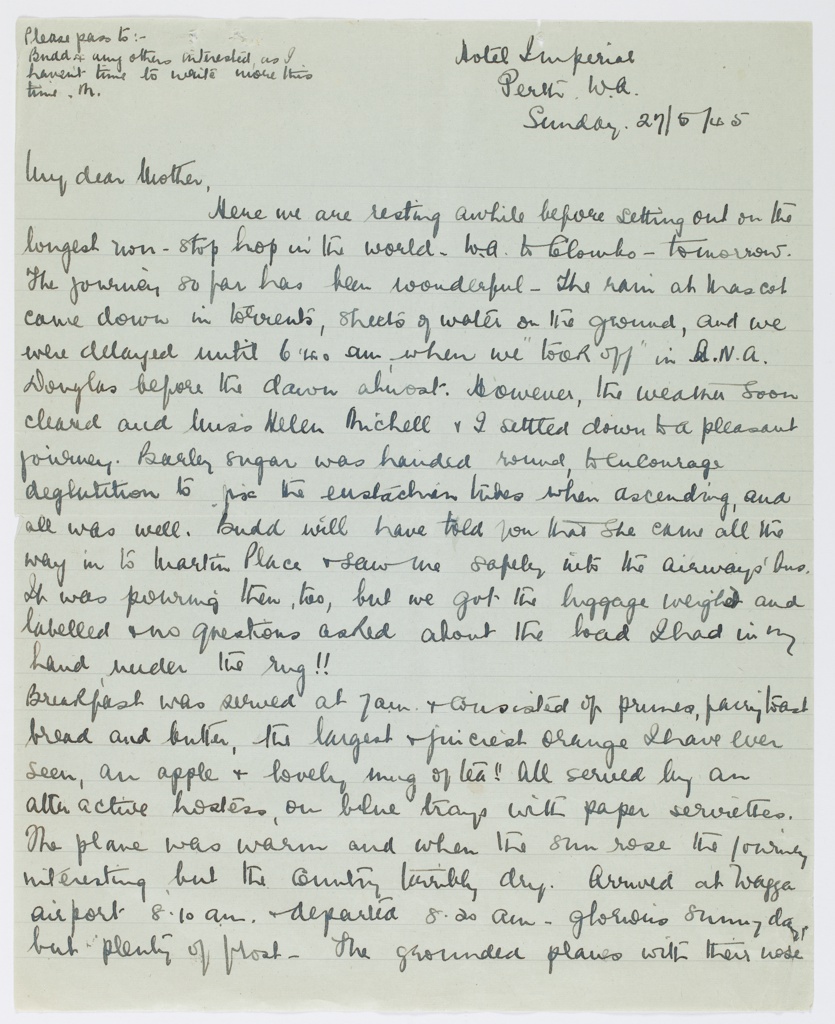

Crucial sources such as diaries or letter correspondence are usually extremely rare, and interviews conducted years, even decades, later can potentially lend itself to a degree of containing slight inaccuracies (usually of minor details within the broader picture). Therefore, with the absence of the former, I have relied mainly on primary sources, including war records and contemporary newspaper accounts, as the core basis for a biographical history. Whilst Catherine Kenny’s extensive interviewing accounts on the Australian POW nurses in Malaya and elsewhere is indeed a valuable asset, in this area, I have consulted instead the Sydney Morning Herald and Women’s Weekly contemporary accounts and interviews conducted immediately after their release in September 1945. The Prince Henry Hospital Museum importantly also showcases on display their former Coast-Prince Henry nursing staff and graduates that had served in wars and conflicts abroad. Originally, this project was to convey the histories of at least four nurses from the former hospital. However, both Nora Kathleen Fletcher and Muriel Knox Doherty were reluctantly eliminated mainly due to exceeding word count limits thereby inhibiting other important detailed aspects: also, the former had worked entirely with the (British) Royal Red Cross and St. John Order throughout the First World War; whereas the latter had already extensively written about her experience from her own exemplary seven hundred page letter correspondence (as a United Nations rehabilitation nurse at the Belsen concentration camp in the aftermath of the Holocaust) which has also thus been expanded by the authors Judith Cornell and Lynette Russell. By these inclusions, it would have therefore somewhat undermined this project by negating the all-encompassing ANZAC element, as well as forgoing the crucial aspects from those necessary unpublicised accounts.

Henceforth, the fundamental themes are a sterling appreciation for cherishing Australia’s national heritage through an inherent understanding of its national identity forged through the ANZAC spirit of ‘mateship,’ and commemoration of its war legacy. By illustrating these war nurses’ biographical profiles, it serves as the fundamental need as a memorial towards the Prince Henry museum itself and the overall general public The museum will, hopefully, proudly identify within its own history how it had become inexorably linked with the ANZAC legacy in which it can inviolably claim its own contribution to its story. For the public, it will hopefully serve as a continuing additional layer of storytelling about the ANZAC legend that is subconsciously ingrained within the Australian psyche and cultivated by its national pride. It also further helps us to bring this historical past into our own present understanding of our Australian identity. As Anna Clark stipulates in Private Lives, Public History, it allows a means of “map[ping] that historical space not only as disjuncture but also as a possible intersection.”