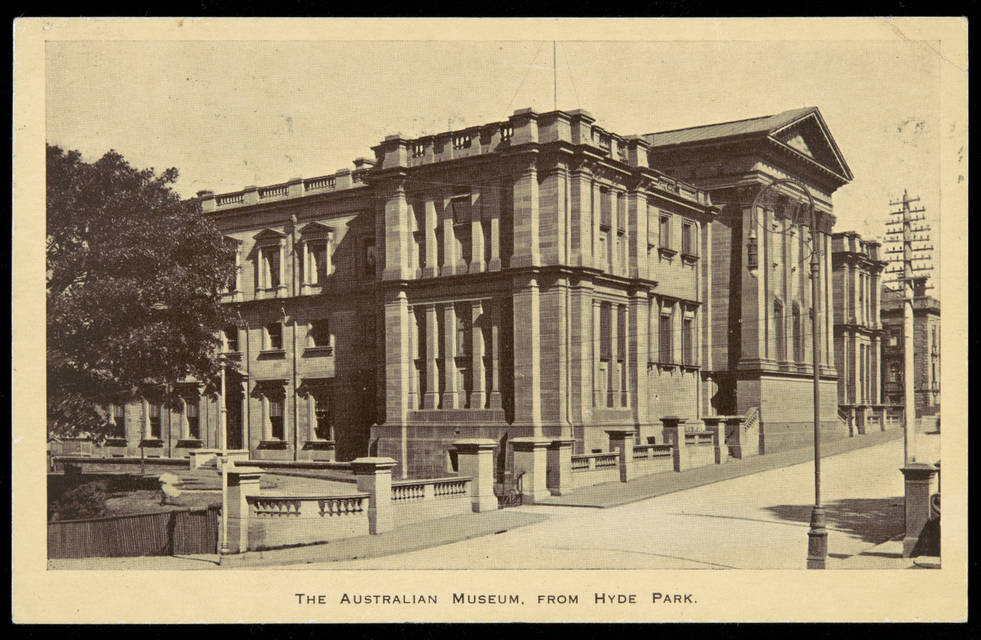

The Australian museum sits on the corner of College St and William St. A colonial monolith overlooking the leafy boulevards of Hyde Park, and beyond that, Sydney’s crowded wall of skyscrapers. The museum has a resolute squareness, reiterated by the pockmarked sandstone blocks that constitute its thick and impressive walls. Clad in a contemporary armor of shinning glass and commercial billboards, the museum’s original steeped roof peaks out, still visible. This roof is evocative of the museum’s role as a mega-house—home to ancient fossils, sparkling gemstones and taxidermied Australian wildlife carefully stitched into time.

Many of us brought to museums as children, can if prompted, tap into the imaginative richness of museum spaces. The sacredness that is attached to objects put behind glass permeates the rest of the museum—this is a space of superstition, of discovery, of life and death. This reverent atmosphere, perpetuated by the likes of Night at the Museum (clearly a cinematic marvel), foregrounds the museum’s role as holder of old stuff—irreplaceable stuff—stuff that is meaningful because it informs us of who we are (should those objects be dragged out of storage and brought into the unbearable light of being).

And that’s where the fantasy becomes more complicated—because often, museums in Australia fail to capture public imagination. And this might lead us to question whether the Australian Museum’s heritage as an ‘institution’ deters people from seeing its vibrancy and currency. Kathleen McLean draws on characterisations of museums as knowledge fortresses. But these are fortresses being torn apart by a battling curatorial/public division or “expert-novice polarity”, and the new(ish), far more dynamic AGE OF INFORMATION (i.e the internet).

When I visit the Australian Museum, I am tucked away in a snug corner where chatty librarians and loyal volunteers stop for tea and ginger biscuits on the hour, and it begs the question, is this a museum where a dynamic flow of information and vibrant public discussion is possible? How different is the museum from the university when it comes to going beyond the classroom?

My project with the Australian Museum (so far) will focus on the archive of Elizabeth Pope (1912-1993). Elizabeth Pope was a marine biologist who rose through the ranks to become the first female deputy director of the Australian Museum in 1971. Her career and her scientific ambition stand-out as significant. She began working at the museum at a time when women were expected to leave the workforce once married. On fieldtrips throughout her life she traversed the eastern coastline of Australia, paying attention to the rocky-shore and other sea-life minutia in ways that exceeded the attempts of many of her European male predecessors.

Many of her scientific reports in the archive contain black and white photographs of the sites she surveyed in Australia. This ‘scientific’ photographic archive contains the occasional portrait of Pope with her trousers rolled to the knee and her hair mussed by sea breezes. Her scientific endeavors breached the professional divide between work and leisure, and for me, they speak to a quintessentially Australian way of life.

Elizabeth Pope

Photographer: A nursing sister of the N.T. Medical Service © Australian Museum

Pope’s role in the museum, and in other public spheres, relates directly to the structure of History Beyond the Classroom. Pope was a professional who was required to reach beyond the walls of the museum to engage with broader public interests and scientific endeavours. One of her most notable outputs was Australian Seashores (1952). Written by Professor W.J. Dakin, Pope and her colleague Isobel Bennett (only ever acknowledged as ‘assistants’) were charged with seeing the book come to fruition after Dakin died in 1950. It was the most comprehensive book published about the Australian sea life on the rocky shore and was reprinted 12 times.

Interestingly, Pope’s memorialisation has been less resounding than that of her contemporary Isobel Bennett. Bennett was a self-taught marine biologist, who through determination and a bit of luck carved herself a lasting legacy in the marine biology world. And to me, it begs the question, why? Is it because Bennett was more publically engaged than Pope? Is it because Aussie nostalgia has favoured Bennett’s story of rags to riches—a story that feeds off unfettered optimism and a belief in the fair go? Was her intellectual output more impressive, or more useful? Did people simply like her personality better? Or was it because Pope’s position inside the museum cut her off from public memorialisation?

Whatever the reason, my project intends to draw Pope’s legacy out from the shelves of the museum into a useable form—in ways that are hopefully engaging, and maybe even fun.

As explored by Anna Clark in Public History, Private Lives, public history is about personal connection—its selfish. People are more connected to events and people and places that they themselves have experienced or feel some intangible link to. Thus, a potential direction for bringing relevancy to Pope’s work is to reconnect it with the places she based it in—especially the ones located in Sydney. I think her photo archive will offer me an ‘in’ here. The audience I am considering is of course the community of working scientists that may be interested in the story of a key player in their own history, as well as a more general public interested in an adventurous woman who contributed valuable knowledge to how we understand seashores in Australia.